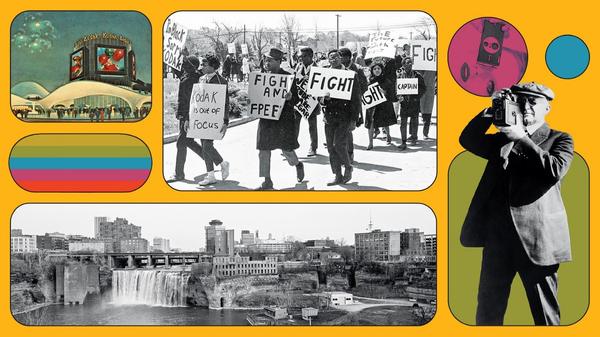

Above, clockwise from bottom-right: Kodak founder George Eastman takes a picture, circa 1925. High Falls in Rochester, New York, Kodak’s hometown. Postcard of the Kodak Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair, 1964. FIGHT, a group seeking to change Kodak’s hiring practices, protests at a shareholders’ meeting, 1967.

This article was published online on June 16, 2021.

This is where Kodak, the doomed photography company, will be pivoting to drugs, I thought, climbing into the hot van. I was struck by a creeping feeling that nothing is impressive and everything is weird. Soon, if all goes according to plan—and Kodak insists that all will go according to plan, with or without the $765 million federal loan—Kodak will upgrade that building by pulling out its guts; putting in new floors, air locks, and control systems; and replacing certain glass-lined reactors with ones made of stainless steel. This makes sense. Kodak is a chemical company—photographic film has hundreds of material components, after all—and it has the experience and the chemists (and the outfits) to make all kinds of chemicals for drugs. Later, in an email, a Kodak spokesperson asked me not to identify the brown building too specifically, for security reasons, so I won’t. (The uranium was stored under Building 82, as reported by CNN.)

All of this, what little of it there is, is likely riveting only if you’ve been steeped in the local history against your express consent. Rochester was founded as a mill town after the Revolutionary War, but boomed with the opening of its section of the Erie Canal in the 1820s, an event about which there is a famous and unnerving song that my classmates and I were required to learn and perform. Like any city, it has cultivated grand and sometimes silly self-mythologies. Once called “Flour City” in honor of its status as the country’s leading producer and distributor of flour, Rochester was renamed “Flower City,” supposedly because of an abnormal concentration of garden nurseries, which remains a point of confusion for residents 150 years later. As a child, I was told that the Genesee River, which cuts through the center of the city, is the only river on Earth besides the Nile that runs north. (It turns out that a lot of rivers run north.) Rochester has an arched aqueduct, just like Rome, and an abandoned subway system full of ghosts, and it once had a famous daredevil, who survived jumping from the top of Niagara Falls but died jumping from the High Falls along the Genesee, in November 1829, with a crowd looking on. (In the spring, legend has it, a block of ice enclosing his corpse turned up on a suburban riverbank.)

Rochester was also where the prosperity of early manufacturing gave Frederick Douglass the patronage required to found his newspaper The North Star and allowed Susan B. Anthony the leisure time to organize for suffrage. The region was a locus of the Second Great Awakening; Jell-O was also invented there, as was the rumor of a generations-long Jell-O curse.

And then, one day, there was Kodak. The first camera for ordinary people was a long black box, about the size of a loaf of bread, introduced in 1888. It was marketed with advertisements meant to convey ease of use—in the images, both women and children were using the cameras successfully. “You press the button, we do the rest,” the ads promised, which was God’s honest truth: Once an amateur photographer had used up the film in her camera, she mailed the entire thing back to the Kodak factory, then awaited her pictures and a reloaded machine. Kodak’s advertising made personal photography a national phenomenon, a new way of seeing and remembering daily life. “Prove it with a Kodak,” one tagline went. “A vacation without a Kodak is a vacation wasted.” “Let Kodak tell the story.” In time, Kodaking became a verb, as natural as Instagramming. Many early Kodak ads mentioned the company’s location, planting it firmly on the map: “Rochester, New York, the Kodak City.”

The business model was simple: Distribute tens of millions of cheap cameras—at times even giving them to children for free—and create lifelong customers for the far more lucrative product, film. And wealth made Kodak ambitious. The company created the film formats of Hollywood; invented the Super 8 technology, which inspired the age of home movies; and built the photosystems that would map 99 percent of the moon’s surface. To the Office of Strategic Services during World War II, it offered teeny-tiny cameras that could fit into matchboxes, for spy stuff. “Kodak was the eyes of the world for over 100 years,” Steve Sasson, the inventor of the first digital camera and one of the company’s most famous employees, told me. Throughout the 1960s and ’70s, Kodak sold 70 million of its $16 Instamatic cameras, and the average owner used eight rolls of its signature Kodapak film each year. The most famous recording of John F. Kennedy’s assassination is on 8-mm Kodachrome film, captured by a random bystander in Dallas, Abraham Zapruder, who was filming because he had the opportunity to film—the Kodak mindset.

Read: The summer of Super 8, and its technological origins

In her 1977 book On Photography, Susan Sontag saw cameras as a tool of “colonization” after the opening of the transcontinental railroad. She commented on the signs that Kodak put at the entrances of various towns, providing suggestions to tourists of local attractions they might wish to photograph: “Faced with the awesome spread and alienness of a newly settled continent, people wielded cameras as a way of taking possession of the places they visited.” Similarly, Kodak laid claim to the American imagination with its “Coloramas”—18 feet high and 60 feet wide—in Grand Central Terminal, in Manhattan, which were swapped out every three weeks and reportedly elicited an “ovation” from passing crowds. Many of those images depicted the adventurous and still-mysterious West. In 1961, Ansel Adams contributed a photo of an Oregon wheat field—he participated because he found the project “technically remarkable.” The rest of the Coloramas were Kodak’s vision of ordinary American life: a Texas family in a convertible, a beauty pageant in Alabama, a family swimming pool in New York (Rochester, of course).

In the famous Kodak episode of Mad Men, which aired in 2007, the ad guru Don Draper wows his clients by coming up with the name for the Kodak Carousel slide projector, filling it with photos of his own gorgeous family and reciting a dictionary definition of nostalgia as he flicks through them. As usual, he’s extremely moved by his own words, feeling things he struggles to feel outside an advertising context. The pitch resonates because Kodak didn’t just teach Americans to take photographs; it taught them what to take photographs of, and it taught them what photographs were for.

The Kodak mythology, though powerful, was and is easily seen through. In the final year of the Coloramas’ installation at Grand Central, The New York Times’ Andy Grundberg composed a eulogy for them, lightly mocking the “idealized pseudo-snapshots of happy families doing happy-family things.” Still, Grundberg admitted, more people had probably looked up at the Ansel Adams photograph in the train station than had ever deliberately sought one out in a museum. The landscapes were wonderful. The effect couldn’t be denied. It’s a cliché at this point to say that there is “something very American” about any particular event or idiosyncrasy, which is maybe why it’s unsatisfying to say that the Coloramas were very American. But in their obviousness I think they were even more very American than they looked: Nobody was really duped, but at some level people wanted to be, or at least they had to concede that the effect was impressive.

In Rochester, Kodak was nothing less than the 20th century itself. Kodak Tower, a 19-story neo-Renaissance skyscraper, was the gilded beacon of downtown. By the postwar period, the company had developed a reputation for generosity toward its employees, paying health-care costs not just for retirees but for their entire families, as well as subsidizing advanced degrees, providing mortgage loans, and organizing employee sports leagues. By the end of the ’70s, Kodak employed more than 50,000 people in Rochester, and things were so good that Flower City became known as “Smugtown.” In 1980, Kodak celebrated its centennial with a summer-long birthday party of free music and fireworks.

From the May 1998 issue: Photography in the age of falsification

For a long time, the prosperity looked like it would hold. In the early ’80s, Kodak was responsible for about a quarter of the economy in Rochester, according to Kent Gardner, an economist at the Center for Governmental Research, a nonprofit consulting firm based in Rochester and originally funded by George Eastman himself. “There were tens of thousands of direct jobs, plus indirect jobs from supplying materials and other services, then the yearly bonus flooding into car dealerships and appliance showrooms,” he told me. “In 1980, the bonus was, in current dollar terms, $450 million of purchasing power landing in the people’s hands at one time.” Nowhere was the symbiotic relationship between Kodak and its city more obvious than in the pages of Rochester’s local newspaper, the Democrat and Chronicle. The space dedicated to letters from the community was often filled with discussion of Kodak’s latest triumphs or challenges, almost always with a sentiment of shared fate. In 1989, as Kodak was skidding through a significant rough patch, an employee named Robert J. Hogan wrote to the paper: “If 20,000 Kodak people volunteered 20 minutes per day, it would amount to 1,660,000 volunteer hours per year donated to the company, to us, to our future.”

This letter was sent in at a time of particular turmoil: The company had failed to produce its own videotape camcorder, a fact that competitors in Japan were profiting from handsomely, and it had been late to instant photography, which had led to a $12 billion patent-infringement suit filed by Polaroid. (Kodak ultimately paid $925 million, at the time the largest infringement payout ever.) Kodak had also just spent $5 billion to acquire Sterling Drug, a pharmaceutical company, to diversify its business—a baffling move to many onlookers; a few years later, Kodak sold the company. There had been several rounds of layoffs throughout the decade, including a cut of 4,500 jobs in 1989 alone. A briefly promising union-organizing effort, led by the International Union of Electrical Workers, petered out, as employees expressed fear of retaliation by an openly anti-union company.

But to the extent that Rochester residents expressed distress about any of this, they focused their ire on specific executives, never on the company itself. Several letters to the newspaper at that time called for CEO Colby Chandler to resign—and quick, lest his epitaph read The Man Who Killed Kodak. This would soon reveal itself as a miscalculation. In 1990, Chandler retired and was replaced by a new CEO, Kay Whitmore, who promptly gave an interview about his positions on the company’s urgent issues. Among other things, he said that he saw some legitimacy to the recently floated argument that Kodak’s headquarters should be moved out of Rochester. Stockholders and board members were justified in their “frustration” with the city, he went on, and with the notion that Kodak owed Rochester the generosity it had so freely shown. “Communities are not really entitled to that sort of thing,” he explained.

In 1993, the year I was born, the blood was in the water. Kodak replaced Whitmore—who had not been cutting costs quickly enough—with a former head of Motorola, George Fisher, the first person to lead the company who hadn’t lived most of a lifetime in Rochester. The company laid off 10,000 people in Fisher’s first three years. Then it laid off another 10,000. As consumers moved beyond film photography and started to favor digital, Kodak was slow to adapt. Back in 1989, Steve Sasson had shown Kodak’s management a version of the digital camera he and other Kodak researchers had spent 15 years perfecting, and management had turned him down flat. “That’s when I kind of got frustrated,” he told me. “If we could do it, other people could do it. But Kodak was reluctant. You could never project a financial business model that was superior to photographic film.” So, by 1993, Kodak had spent $5 billion on digital-imaging research, yet that year it only reluctantly entered the digital-camera race—neck and neck with competitors like Sony, Canon, and Olympus, not miles ahead, as it could have been. And it failed to rearrange its business model to make the new cameras profitable. In 1997, Fisher was trying to push the company to succeed in digital while still placating its internal old guard and insisting that “electronic imaging will not cannibalize film.” In 2001, according to a Harvard case study, Kodak was losing $60 on each digital camera it sold.

Read: What killed Kodak?

By the time Kodak filed for bankruptcy, in 2012, it employed just over 5,000 people in Rochester. Soon that number was cut in half. Retirees lost their health care, and many of them lost their pension. Remaining employees could look forward only to more layoffs, and local nonprofits and cultural institutions had to think of someplace else to approach for support.

Kodak has since made many efforts to come back: Leaning into commercial printers. Selling off patents. Trying to break into the smartphone game, and then trying again, but uglier. (The Kodak Ektra, announced in 2016, was a smartphone that was supposed to look like a camera from 1941. The technology website The Verge compared the aesthetic result to “an insect that eats the insides of its rivals and then wears their hollowed-out corpses like trophy armor.”) A few years ago, Kodak was leaning into its history, making a new Super 8 camera and a collection of retro jackets, fanny packs, sports bras, and other items with the fast-fashion brand Forever 21. “I have this ambition to return Kodak to being one of the world’s best-known, best-loved brands,” the chief branding officer, Dany Atkins, told me at the time. She doesn’t work at Kodak anymore. Neither does the CEO who hired her.

Kodak continues to sell film, but now it calls itself a chemical company. Its pared-down workforce focuses primarily on commercial printing (everything from newspapers to food packaging) and, to a lesser extent, on an array of specialty products: X-ray films; fabric coatings; antimicrobial materials; and, more recently, films that can be used to manufacture printed circuit boards, like the ones in ventilators. It also sells film for the type of high-altitude cameras that can be used in reconnaissance planes. “What they use them for is classified, but it’s not classified that we make the film and sell it to the U.S. government,” Terry Taber said.

The company is still innovating, filing new patents for ink compositions and “nanoparticle composites,” as well as processes for high-speed printing—it says that its inkjet printers are the fastest in the world, and that they can print on surfaces no other company’s can—but it is generally not inventing splashy products that are meant to charm the average American consumer. “Anytime people hear about Kodak coming back, they think it’s coming back to be the Kodak it was when they were a kid, or when their mom was working there or something,” Sasson told me. “I don’t foresee that.”

Former employees still pine for that Kodak, some of them gathering in Facebook groups to reminisce. “I used to walk down the dark halls and think, This is manufacturing,” Marla Dudley, a 67-year-old retiree, told me. “I was so proud.” Her story was similar to what I heard from almost everyone I spoke with: She started working at Kodak when she was young; she climbed the ranks at Kodak; she retired from Kodak. It was the only employer she ever had. Patricia Loop, 65 and retired, told me that her father worked at Kodak, as did her grandfather, her sister, and her first and second husbands. “I made more money than most of my friends and got everything I wanted,” she said with a laugh. These people didn’t exactly miss working—they were happy to be retired—but they were disappointed that the Kodak way of life is over.

The Kodak way was paternalism, a term that was first intended affectionately. Back in the day, George Eastman offered his employees a lifelong pension and an annual profit-sharing bonus in exchange for their loyalty and the surrender of any ideas about collective bargaining. Kodak sometimes put off making big technological changes until it could retrain employees so they could keep their jobs, the historian Rick Wartzman wrote in his 2017 book, The End of Loyalty: The Rise and Fall of Good Jobs in America. In the late 1950s, the company waited five years to install a new kind of film-emulsion coating machine so that workers who would have been made redundant could first reach retirement age and move gracefully on to pension payments. These pensions were “the ultimate expression of how the social contract between employer and employee was based on an expectation of lifetime loyalty,” Wartzman told me. “You’d work hard until you couldn’t work anymore, and then they’d take care of you forever.”

Today, in some ways for the better but mostly for the worse, work looks nothing like that. None of this social-contract talk even resonates with me. The first thing I read about my fate as a Millennial was in a magazine that had been left on a chair in my college library. I don’t remember which magazine, or who wrote the story; all I know is that it used a still from Girls and that the author informed me I would make lateral career moves all my life, having many jobs and many different employers and sometimes a good amount of money and sometimes very little, and also no loyalty, and no personal character built off a relationship with one company. I accepted this as reality.

Read: Kodachrome dies at 74, and why we should mourn

“Kodak was an exemplar of something that was pretty standard among large employers at the time,” Wartzman said. Sounds fake, but okay, my internet brain responded. Workers “were able to take part and get more of their fair share of the country’s economic gains,” he explained. “People look back on that time in Rochester nostalgically because that’s what a lot of people are hoping the country can somehow find its way back to.”

But in truth, to ache for Kodak’s past in Rochester, you have to indulge in some revisionist history. The vaunted mid-century prosperity and surety were really only for white men—and Kodak’s generosity was often two-faced. This was publicly apparent as early as 1939, when the New York legislature’s Commission on the Condition of the Colored Urban Population investigated why the Black citizens of upstate manufacturing cities remained so impoverished, despite a recovering economy. The report called out a “manufacturer of photographic equipment and supplies” with a payroll of 16,351—Kodak—for employing just one Black person, as a porter (in addition to 19 Black construction workers through a subsidiary). The numbers for other large manufacturers in the area at the time were no better.

Justin Murphy, an education reporter at the Democrat and Chronicle, is working on a book about this lesser-known history of Rochester, which he argues is a root cause of the area’s grievous racial inequality and school segregation in the present day. “Kodak just didn’t hire Black people,” he told me. “It was just absolutely not something they were interested in doing.” Like other local power brokers at the time, Kodak also played a direct role in the region’s housing segregation, by building developments in Rochester’s suburbs specifically for its employees and helping them finance home purchases. In the property deeds for at least one major development, called Meadowbrook, a covenant stated that “no lot or dwelling shall be sold to or occupied by a colored person.” (A Kodak spokesperson said that the company did not have any comment on events that happened decades ago and that today it has “an unwavering commitment to diversity.”)

The Black population of the city grew from less than 8,000 in 1950 to about 32,000 in 1964, and still the region’s largest employers were not providing Black workers with the types of reliable manufacturing jobs that white residents could count on almost as a birthright. Rochester’s overall unemployment rate was below 2 percent at the time, but for the Black population it was 14 percent. Racial tension drew the eyes of the country to Rochester in the summer of 1964, when the use of dogs by the police to control a crowd at a block party incited three days of riots. Not long after, a community group called FIGHT, led by a local minister, Franklin D. R. Florence, and the renowned organizer and provocateur Saul Alinsky, initiated contentious negotiations with Kodak over a job-training program to prepare unemployed Black residents for entry-level positions. At one point Alinsky suggested hosting a “fart-in” at the philharmonic to get attention. More salient was the group’s demonstration at Kodak’s 1967 stockholders’ meeting, in Flemington, New Jersey. The two sides eventually reached an agreement, and a job-training program was promised. But by 1968, just 4 percent of Kodak’s Rochester workforce was Black—compared with what would soon be nearly 17 percent of the city’s population—and the whole thing was written off by some white residents as unjustified petulance. Letters from the community printed in the Democrat and Chronicle called the dispute the “shame of the city,” FIGHT’s tactics “deplorable,” and its allegations baseless. The paper itself took Kodak’s side, openly. Responding to a complaint from a local rabbi that previous editorials had been “one-sided in favor of Kodak,” the editors wrote, “Good heavens, we hope so!” Years later, Alinsky, in a magazine interview, looked back on the events in “Rochester, New York, the home of Eastman Kodak,” and applied some practiced rhetorical torque: “Or maybe I should say Eastman Kodak, the home of Rochester, New York.”

Today, Rochester is a different place. Murphy, the Democrat and Chronicle reporter, asked me to correct the record: “Often when we read about Rochester in the national media, it seems like the writer thinks … all we ever do is walk around and cry about how Kodak is gone.” So, in print, here it is: People who live in Rochester do many things other than walk around and cry about how Kodak is gone.

Though they do talk—sometimes, not crying, just talking—about how bad it is that Kodak is gone. “I don’t think anyone ever imagined that the industry would change as rapidly as it did and that we would experience the economic decline that we did,” Mayor Lovely Warren told PBS in 2019, after mentioning that her mother had worked for Kodak. The same year, Gardner, the economist, published an analysis of Kodak’s “long shadow” over the local job market, writing in the Rochester Beacon that “Rochester’s growth in real GDP from 2007 to 2018 was effectively zero,” compared with a national growth rate of 16 percent.

When I asked Warren what people tend to get wrong about Rochester, she said that the city has been “written off as a has-been” just because it’s no longer affiliated with a flashy Fortune 500 company. As in many post-manufacturing cities, Rochester’s largest job providers are now its universities and its health-care system. The University of Rochester has a renowned medical school and is also home to a famous laser lab. In recent years, the city has had luck with optics-related start-ups and enjoyed the government’s interest in its photonics talent and its nuclear-fusion research capabilities. Rochester has also attracted the attention of the MIT economist Jon Gruber. In a 2019 book, Jump-Starting America, Gruber and his co-author, Simon Johnson, proposed massive federal grants to create new science and tech hubs in mid-size American cities. They argued that Rochester would be an ideal candidate for investment because of its affordability and its concentration of respected colleges.

But Gruber and Johnson’s analysis did not consider several other common measures of a city’s health, such as metrics related to income inequality, trust in government, and high-school education. Rochester is struggling with all three. Today, the poverty rate—31.3 percent—is roughly triple the national average. Mayor Warren was indicted on two felony campaign-finance violations in October 2020 (she maintains her innocence and has called the accusations a “witch hunt”), compounding a crisis of public faith in her leadership that followed the death of Daniel Prude, a Black man who died of complications from asphyxiation after being restrained by Rochester police earlier that year. (No police officers have been indicted in connection with Prude’s death.) More recently, Warren’s husband, Timothy Granison—from whom Warren is separated, though the couple still live together—was arrested on charges of gun and drug possession and accused of participating in a cocaine-trafficking ring. (He has pleaded not guilty.) Meanwhile, the city school district has faced massive budget deficits in recent years, and its graduation rate, though slowly rising, is about 20 percentage points below the state average. (“You’re right,” Gruber told me, after I asked about the absence of public-education metrics in his book. “I wouldn’t invest in a place like Rochester without a commitment to turn the education system around.”)

“Many people are surprised to learn that we are one of America’s most racially segregated communities,” the Rochester Area Community Foundation and its data-collecting arm, ACT Rochester, wrote in a special report last August. “We have some of the most segregated schools; we have one of the greatest income disparities in America based on race and ethnicity; we have one of the country’s greatest concentrations of poverty.” These are disparities that were arranged in Rochester throughout the 20th century, and have proved themselves durable.

Ann Johnson, the executive director of ACT Rochester, told me that awareness of Rochester’s problems has grown, spiking after the city’s Black Lives Matter protests last year. Those protests, led by city activists, were of a piece with the nationwide outrage after George Floyd’s killing, but they were also motivated by local anger over Prude’s death. They eventually spread to the mostly white suburbs at an unprecedented scale. Last July, a group called Save Rochester organized a march out of the city and onto the interstate that leads east into the wealthiest towns in the area, blocking traffic and commanding attention. That group has since formalized operations, and is one of many agitating for substantive policing reform and reparations-minded wealth redistribution, bolstered by pieces of state legislation.

In the immediate future, Rochester must also figure out how to rebound from the job losses caused by the coronavirus pandemic. But this crisis, Johnson said, has galvanized community groups. Outside observers have suggested this as well, if in a colder, backhanded manner. A recent analysis by the Brookings Institution argued that “legacy cities” like Rochester have an advantage in times of crisis because of their “grit.” In other words: Rochester’s recent past is so grim that its residents should by now be more clear-eyed than people who live in happier places.

After our visit to the manufacturing building, Taber took me to the 14-story structure that houses Kodak’s research labs, where the company plans to create a 36,000-square-foot R&D center for its pharmaceutical work. When the company was in its prime, as many as 2,000 people worked in the building. It was built in 1969, and the vacant reception area has a mid-century-modern look; it seems sort of hip but is perhaps only authentically outdated. As we walked through various lab spaces, Taber explained to me again that Kodak has the experience to produce chemicals for drugs. He seemed aware of the arguments and attitudes that were already set against the proposition: Here is Kodak, trying to reinvent itself again. Really, one more try? Into each silence in my conversations with Taber or the men who led us around the business park, the reassurances would inevitably come: We’re qualified to do this, and it’s going to work. We’re a chemical company.

After the tour, Jim Continenza told me the same thing over a Google Hangouts call. He does not live in Rochester, and was in Florida when we spoke. “We’ve been making chemicals for 100 years,” he said. “If you walk through [the business park]—and I think you just did—you will not see an assembly line anywhere. You didn’t see anybody assembling pieces and parts, did you? You saw big reactors and steam pipes.” He spoke briskly, making a series of rapid-fire clarifications about the company’s latest plan, and I recognized the signature sharp candor of people who have been on the defensive for so long that they no longer care about sounding polite. Kodak has been making components for pharmaceuticals for five years already, Continenza said, and it will keep doing so, with or without a federal loan. Kodak could play “a very, very important role” in fixing the nation’s broken pharmaceutical supply chain, he argued. “It’s very interesting how we’re not qualified to do it, yet we’re doing it.” Then he reminded me again that Kodak is a chemical company. “I think we’ve made one camera in 100 years—I’m making that up; I don’t even know,” he said, then tossed in a revision: “Yeah, we did invent the digital camera that killed the company.”

Actually, Kodak has made many different cameras over the past century—and licenses its name to many more—but I take his point. Continenza sees the commercial value of Kodak’s brand, but is not interested in its emotional resonance. Today, Kodak is not an icon of Americana but an interesting collection of remarkably capable scientists, with a history of coming up with new things to do with chemicals. “In the last 100 years, Kodak has received over 20,000 U.S. patents,” Taber told me. “If you look at where our invention is, where our innovation is, its foundation is in science and chemistry. In order to make money, you have to make businesses out of what you can invent and make.”

It now seems unlikely that Kodak will ever receive the $765 million loan. When I toured the property, Taber would say merely that Kodak would renovate its facilities even without the funds—“it will just be a different scale and a different pace.” (Kodak has since raised more than $300 million in new capital from other investors, some of which it says it might use for the pharmaceuticals business.) In September, an outside law firm finished an investigation into the federal loan guarantee without finding evidence of anything illegal, but Democratic lawmakers questioned that conclusion. An investigation led by the Development Finance Corporation’s inspector general took longer, wrapping up in December, also without finding evidence of wrongdoing, though the agency acknowledged in May that the loan was still on “indefinite hold.” There have been no updates on a simultaneous investigation by the Securities and Exchange Commission since it was announced last August. In May, a Kodak spokesperson said that the company was no longer expecting the loan “given the time that has elapsed,” and downplayed the importance and scope of pharmaceuticals in Kodak’s overall business.

After my tour of the business park, I went back to the Eastman Museum, which was in the process of building a large new entrance. I wanted to see if it matched my memory. The house itself looked smaller and less grand, and the elephant head in the main room—a reproduction of the taxidermied one Eastman had hung, which, decades ago, mysteriously disappeared—looked goofy. But there were still a few wonders: the sprawling gardens, the pristine library, and, in that low-ceilinged room on the second floor, the suicide letter. The display around it included a handwritten note from Eastman requesting to be cremated, a duplicate of his death certificate, and a small pile of metal. Unlike many of the objects in the museum, the metal pieces weren’t bequeathed by Eastman or donated by his family. The fragments, metallic bits from his coffin that survived cremation, had been tucked away for decades. According to the museum curator, a police officer had scooped them up and saved them, the same way you might save a newspaper from the day of some spectacular event, or a sock left behind by a pop star.

The museum curator also provided me with a map for a self-guided driving tour of everything in Rochester that might not exist without George Eastman: the art gallery, the music school, the hospital, the parks, the bridge, the YMCA, the children’s center, the college my dad graduated from, the college my sister was currently studying at. That wasn’t the whole list, but at this point I’m repeating myself. Okay, okay, I thought.

When I asked former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers to speculate about Kodak’s future, he said that “excessive nostalgia” had led to the company’s downfall, and he wasn’t focused on what might come next. “Kodak is no longer an institution that is of great significance for the American economy,” he told me. I don’t know why I was so interested in hearing a different story. I never worked at Kodak, nor did anybody in my family or, for that matter, anyone I know. But I like listening to any Kodak story for a little bit at a time, to remind myself that I’m susceptible to “excessive nostalgia,” which may be the same thing as what Joan Didion once called “pernicious nostalgia.” When you zoom out, there are moments in which the symbolism is too good: the Coloramas replaced by an Apple store; the cameras that now wander around on Mars, which Kodak this time had nothing to do with; the lunatics of Reddit juicing stocks for all the other golden oldies—the movie theaters, the mall brands, even Nokia—but refusing to spare a thought for a comeback by Kodak.

Zooming back in to Rochester, there are fewer startling images and less drama, replaced by the unglamorous organizing and the incremental progress that is more characteristic of 21st-century urban life. An initiative called Confronting Our Racist Deeds coalesced last year to revoke and replace the property covenants pertaining to homes in Meadowbrook, Kodak’s former housing development in the suburb of Brighton. The covenants in the deeds hadn’t been enforceable since 1948, but several hundred of them were still there, which residents said was a kind of symbolism they didn’t want to continue living with. “The reality is that the impact of these deed restrictions is felt for generations,” an organizer named Johnita Anthony told the local paper after the group succeeded. This episode is one moment in a new story—about an American city that was once synonymous with an American company, quietly coming to stand for something of its own.

This article appears in the July/August 2021 print edition with the headline “The World Kodak Made.”