Economic growth over the past 1000 years can be viewed as sporadic, but a persistent trend is that over the past few centuries, countries of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have fared better than their peers1. For centuries, scholars have explored theories to explain the causes of economic growth, with investment in human capital2 representing a key tenet more recently. Interestingly, the last several decades have also witnessed a consensus of thought on human capital investment as a key driver of income growth and inequality at the individual level3. Indeed, within certain circles, scholars have argued that the most important investment society can make in its citizenry is to increase their investments in early childhood education4.

What remains unsettled, however, is why such investments remain low among certain populations and what should be done to promote them. While the literature reveals that parental investments in children are one of the critical inputs in the production of child skills during the first stages of development5,6, evidence also shows that such investments differ across socioeconomic status (SES hereafter)7,8,9. Even though these differences have been consistently observed across space and over time, serving to exacerbate the rising educational and income inequalities that are commonly observed in modern economies, we know little about the policies needed to address their underpinnings.

This paper takes a step back to examine sources of the disparate parental investments and child outcomes across SES to reveal one potential mechanisms for closing these gaps. We begin by presenting an economic model that invokes parents’ beliefs about how parental investments affect child skill formation as a key driver of investments10. We then add empirical content to the model by focusing on the first few years of life, when parental investments in children have been found to play a crucial role11,12,13. To do so, we design two field experiments to explore if such parental beliefs are malleable, and if so, whether changing them can be a pathway to improving parental investments in young children. In the first field experiment, over a 6-month period starting 3 days after birth, we use educational videos informing parents about skill formation and best practices to foster child development. In the second field experiment, we test a more intensive home visiting program using assessment-based coaching and feedback for 6 months, starting when the child is 24–30 months old.

We operationalize our first field experiment by leveraging the health care system. More specifically, we built partnerships with 10 pediatric clinics predominantly serving low-SES families in the Chicagoland area and leveraged the early well-child visits. The intervention is easily replicable and relatively low-cost. In the second field experiment, we provide a home visitation intervention to low-SES families recruited in medical clinics, grocery stores, daycare facilities, community resource fairs, and public transportation in the Chicagoland area. In both cases, we measure the evolution of parents’ beliefs about the impact of early child investments, parental investments and child outcomes at several time points before and after the interventions.

Our analyses point to several unique insights. First, we show that there is a clear SES-gradient in parents’ beliefs about the impact of parental investments on child development. A second result provides evidence that these disparities matter, as parents’ beliefs predict later cognitive, language, and social-emotional outcomes of their child. For instance, we find that parental beliefs about the impact of early child investments alone explain up to 18% of the observed variation in child language skills. A third insight is that those parental beliefs are malleable. Both field experiments induce parents to revise their beliefs about the impact of early child investments. Furthermore, exploiting the random information shocks generated by the experiments, we show that belief revision led parents to increase their investments in their child. For instance, we find that the quality of parent-child interaction is improved after the more intensive intervention (and to a smaller extent, after the less intensive intervention), and we provide evidence of a causal relationship with changes in beliefs about child development. Finally, we find positive impacts on children’s interactions with their parents in both experiments, as well as important improvements in children’s vocabulary, math, and social–emotional skills with the home-visiting program months after the end of the intervention. These insights represent a key part of our contribution as they show that changing parental beliefs about the impact of early child investments could potentially be an important pathway to improving parental investments in children and, ultimately, child outcomes.

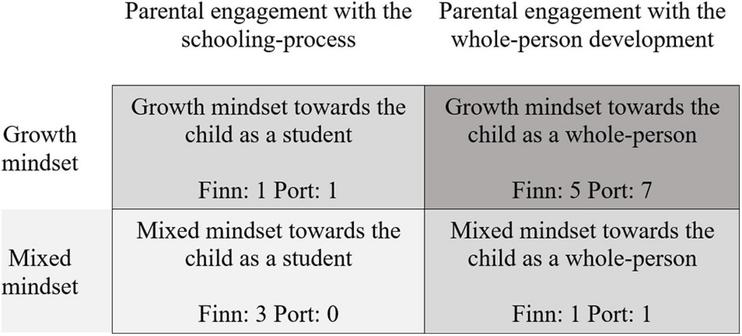

Our work speaks to several branches of the literature. First, it contributes to the literature on parental beliefs by exploring the mutability of such beliefs. Research in Developmental Psychology has found that parental beliefs about child development can predict parenting practices, home environment and child outcomes14,15, and also explain socioeconomic disparities in parental language inputs16,17. Recently, the economics literature introduced parental beliefs about skill formation as a key factor in models of human capital investments10. This literature shows that such beliefs differ across SES, and that they predict investments in children18,19,20,21,22,23. Not only do we replicate those different findings, but we additionally use two field experiments to demonstrate that parents’ beliefs about the impact of parental inputs are malleable and link changes in those beliefs to changes in investments.

A further distinctive aspect of our study is the exploration of the full chain of impacts, from parental beliefs about child development to child outcomes, of two different types of parent-directed interventions. This approach allows us to focus on two types of interventions and to explore if each can change beliefs, and how those belief changes map into parental behaviors. In this way, our data suggest that smaller changes in parental beliefs about child development are not necessarily enough to induce lasting changes in parental investments and child outcomes.

By focusing on parental inputs, we also contribute to the literature on early language interventions in Developmental Psychology24,25,26,27,28,29,30. These papers show that providing parents with feedback, or coaching, regarding their linguistic inputs can enhance parent–child interactions. Results from our second field experiment confirm those findings in another population, English Language Learners in Spanish-speaking families, and we go one step further by assessing the impact of the intervention on a large spectrum of child outcomes.

The remainder of our paper is organized as follows. The “Results” section explores the roots of early socioeconomic inequalities via two field experiments, summarizing our design and our experimental results. The “Discussion” section provides concluding remarks. In the Supplementary Information, we present our economic framework that provides a critical link between parental beliefs about the impact of early investments, parental investments, and child outcomes, details on the experimental and econometric methodologies, as well as some additional results.