On your iPhone, you can now tap a button that says, “Ask app not to track.” But behind the scenes, some apps keep snooping anyway.

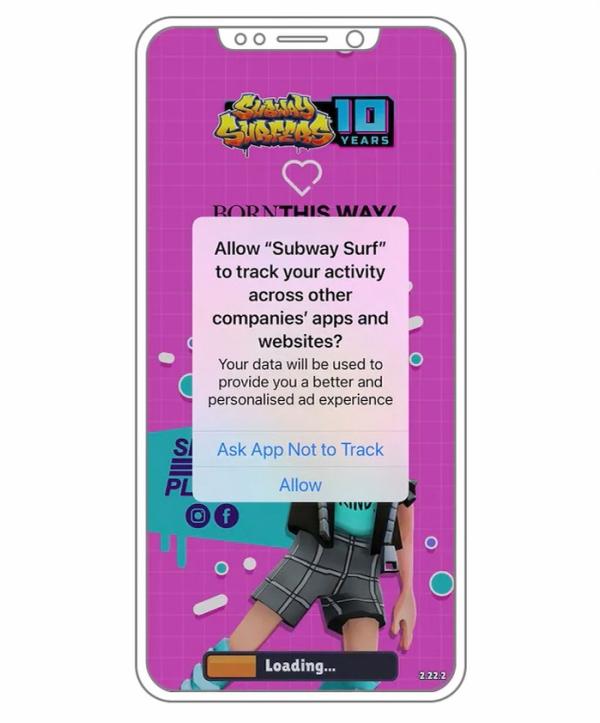

Say you open the app Subway Surfers, listed as one of the App Store’s “must-play” games. It asks if you’re OK with the app “tracking” you, a question iPhones started displaying in April as part of a privacy crackdown by Apple. Saying no is supposed to stop apps such as Subway Surfers and Facebook from learning about what you do in other apps and websites.

Introducing Help Desk: Technology coverage that makes tech work for youBut something curious happens after you ask not to be tracked, according to an investigation by researchers at privacy software maker Lockdown and The Washington Post. Subway Surfers starts sending an outside ad company called Chartboost 29 very specific data points about your iPhone, including your Internet address, your free storage, your current volume level (to 3 decimal points) and even your battery level (to 15 decimal points). It’s the kind of unique data that could be used by advertisers to identify your iPhone, possibly letting them know what other apps you use or how to target you.

In other words, it’s sidestepping your request to be left alone. You can’t stop it. And your privacy is worse off for it.

AdvertisementStory continues below advertisementApple’s rules say apps aren’t allowed to track people who say they don’t want it. So why is this happening? Privacy advocates say this kind of data-gathering is likely tracking, just by a different name: fingerprinting.

Our investigation found the iPhone’s tracking protections are nowhere nearly as comprehensive as Apple’s advertising might suggest. We found at least three popular iPhone games share a substantial amount of identifying information with ad companies, even after being asked not to track.

Help Desk: Ask our personal tech team a question

“Apple believes that tracking should be transparent to users and under their control,” said spokesman Fred Sainz. “If we discover that a developer is not honoring the user’s choice, we will work with the developer to address the issue, or they will be removed from the App Store.”

When we flagged our findings to Apple, it said it was reaching out to these companies to understand what information they are collecting and how they are sharing it. After several weeks, nothing appears to have changed.

What happens when you ask not to be tracked

Apple’s so-called App Tracking Transparency initiative has prompted big app makers such as Facebook and Zynga to complain it could hurt their profits. But that doesn’t mean it has stopped all tracking.

To find out what happens when you tap “ask app not to track,” Lockdown says it tested ten popular apps on an iPhone running iOS 14.8 and again with the newest iOS 15, analyzing what personal information flowed out of them.

As part of a technical change that arrived with iOS 14.5, the apps were no longer able to access one valuable piece of data: a kind of social security number for your iPhone, known as the ID for Advertisers, or IDFA. But there’s other information that can identify your phone beyond that number.

AdvertisementStory continues below advertisementLockdown found most of the apps continued to communicate behind the scenes with a murky industry of third-party data companies that privacy advocates call trackers. You’ve probably never heard of most of them, but they can receive a flood of information from your iPhone, potentially revealing how you use apps and even your location. Their uses for the data could be benign, like helping an app find bugs and track how well its design works — or they could be feeding your information to advertisers and data brokers.

Among the apps Lockdown investigated, tapping the don’t track button made no difference at all to the total number of third-party trackers the apps reached out to. And the number of times the apps attempted to send out data to these companies declined just 13 percent.

“When it comes to stopping third-party trackers, App Tracking Transparency is a dud. Worse, giving users the option to tap an ‘Ask App Not To Track’ button may even give users a false sense of privacy,” said Lockdown co-founder Johnny Lin, a former Apple iCloud engineer.

Even more worrisome for consumers, Lockdown says three of the apps it investigated — Subway Surfers, Streamer Life! and Run Rich 3D — appeared to be collecting data that could be used for a more invasive kind of tracking known as digital fingerprinting.

Fingerprinting happens when an app takes innocent-looking but technical information from your iPhone, like the volume, battery level and IP address. Combined, those details create a picture of your phone that can be as unique as the skin on your thumb.

From the same test phone, all three games Lockdown tested sent ad network Chartboost nearly the exact same array of device-specific data points. (An ad network is a company that serves as a broker between publishers and advertisers.) All three also sent ultra-specific characteristics of the test iPhone to an ad company called Vungle. That could allow app-makers and advertisers to connect the dots and track you without your consent.

Data shared with Chartboost by Subway Surfers, Streamer Life! and Run Rich 3D

Neither Lockdown nor other privacy experts we consulted could say with certainty what was happening with the data flowing out of these apps, or whether it was being used to track people for advertising. Only the app makers themselves can explain what’s happening with your data.

“The list of readouts from Chartboost certainly looks like it could be used to create a fingerprint. But I don’t think there’s a way to know without seeing what comes out the other side,” says Bennett Cyphers, a staff technologist at the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), a digital rights advocacy group.

Few of the app developers would give us clear answers.

“In order for the game to function properly, some data is communicated to Ad Networks,” emailed Sybo, the company that makes Subway Surfers. “As a company, we do not track users for advertising purposes without their consent.” It didn’t specify why it needed to send so much personal information to ad companies to function properly.

The maker of Run Rich 3D did not respond to requests for comment. The maker of Streamer Life! said it was compliant with Apple’s privacy rules.

Chartboost, an ad company owned by game maker Zynga, wouldn’t answer our questions, but it said it is “committed to protecting the privacy of the end users while providing the best experience possible for our publishers to support their revenue streams from advertising.”

Vungle said the data points it received cannot be used “to identify users or discern what other apps they may use.” It said they “serve the practical purpose of ensuring we show an ad compatible with the right device in the right language for the right country and app.” It didn’t explain how data such as battery level helps it do that.

Apple says fingerprinting iPhones has long been against its rules.

What is tracking, anyway?

It’s hard to forbid tracking when there’s little agreement on what “tracking” even means.

Many iPhone owners might assume it means an app taking your data in some way, perhaps including your location. Privacy advocates argue tracking can happen any time an app or website shares your personal information with a third party without your express consent. It’s one more company that could leak or misuse your data. (One recent example is a Catholic priest who appears to have been outed as gay using data likely sent to a third party by the dating app Grindr.)

Apple applies a more narrow definition of tracking: the process of connecting information collected about you on one company’s app or website with information collected by different companies — and only for the purposes of ad targeting, ad measurement or sale to data brokers. It excludes sharing data for other purposes, such as analytics and fighting fraud.

I checked Apple’s new privacy ‘nutrition labels.’ Many were false.

AdvertisementStory continues below advertisementSome in the app industry are promoting their own definitions of tracking while seeing how far they can bend the one provided by Apple.

That’s because for apps that rely on ads, Apple’s tracking protections were bad news. Advertisers don’t want to pay if there isn’t proof their ad prompted people to download another app or make a purchase.

Before Apple’s crackdown, matching up customers with the ads they’d tapped on was relatively easy. But with iOS 14.5 came a giant problem: The technology the industry had come to rely on for tracking — the IDFA number — suddenly disappeared.

Enter fingerprinting. Some in the ad industry use different terms for it. For example, “probabilistic matching” is a way to use personal information harvested from iPhones to attribute ads without knowing the user’s identity for sure.

The practice has divided the app industry. “We are constantly getting pressure from customers who want to do probabilistic matching for opted out users,” says Alex Austin, the CEO of app data company Branch. “We believe that ultimately Apple will take a stance here and crack down on companies that are attempting workarounds.”

Some data companies barely hide what they’re up to.

Lockdown found that two data companies — AppsFlyer and Kochava — built settings that let their clients ignore people’s tracking preferences.

Kochava, a maker of ad performance software, offers a product named “AppleTracker 4.6.1.” Lockdown found that Kochava lets its customers simply toggle a switch to override people’s tracking request. Kochava says the capability was designed so that companies could track customers across apps and websites they own themselves — which doesn’t violate Apple’s narrow tracking definition. But there’s little stopping developers from using Kochava to track across apps made by different companies, too, which would violate even Apple’s rules.

Lockdown found a similar end-run available from data company AppsFlyer. Lin called it a privacy cheat mode. “All it took was clicking a single button,” he said.

Who’s responsible for how this technology gets used? Both companies have warnings on their websites telling app-makers not to abuse their capabilities with people who’ve opted out of tracking — but they don’t technically stop it.

Kochava said: “The guidelines have been authored by Apple and we would expect Apple to enforce them. Default behavior by Kochava is compliant with Apple policies.”

AppsFlyer said, “The app developers are in full control.”

What can be done

Protecting privacy is an arms race.

Some advocates say Apple’s tracking crackdown has made a difference.

“Apple moving from a stance of ‘tracking is sanctioned by default’ to ‘tracking is only sanctioned when a user opts in’ is a big, big deal,” says Cyphers of the EFF.

But if you’re a privacy-conscious iPhone owner, the rise of fingerprinting is bad news.

“Previously consumers had some control over their data — for example, they could at least reset their IDFA and know that they would likely unlink their previous activities from whatever new actions they’re engaging in,” says former chief technologist for the Federal Trade Commission Ashkan Soltani. “With fingerprinting, you have no idea whether or not a company is actually linking your activities — and you have no easy way to stop it if it occurs.”

The open question is what Apple will do about it.

AdvertisementStory continues below advertisementMany app makers and data companies take cover behind Apple, saying if they were doing something wrong, Apple would stop them in the reviews it conducts before allowing them on the App Store.

In April, Apple appeared to make an example out of apps working with a data firm called Adjust, leading it to stop collecting certain data points. But since then, say industry executives, Apple’s enforcement has dried up, and data companies are seeing how far they can push it.

“Apple has not done anything to stop it, so every company moved into doing it,” says Eric Seufert, the founder of a consultancy called Heracles who runs the influential industry blog Mobile Dev Memo.

Apple says it’s the responsibility of apps themselves to follow its rules, but it has rejected tens of thousands for policy concerns related to App Tracking Transparency and fingerprinting.

There’s no escape from Facebook, even if you don’t use it

Without thorough audits, it may be hard even for Apple to know exactly what happens to data after it leaves an app and goes to a third party. Some apps and data companies also take technical steps to hide their code, making it harder to investigate it.

Apps do have to say in privacy policies that they send data to third parties, but often don’t specify to whom or exactly why. The privacy “nutrition labels” Apple started requiring apps to post to its App Store earlier this year also don’t include the names of the companies receiving data.

A new App Privacy Report feature in iOS 15 lets people see what domains are contacted by the apps they use — but you can’t individually opt out of the connections. If you want to try to block trackers, software such as Lockdown, Jumbo Privacy or Disconnect’s Privacy Pro tries to break the connections to companies in the business of tracking.

There’s also some hope Apple might yet come up with technical solutions that make fingerprinting harder for apps to do on its devices. The new Private Relay service Apple is offering as a part of an iCloud+ subscription could pave the way. It obscures IP addresses from web trackers in the Safari browser, a data point that’s often key to app fingerprinting, too.

Unless Apple acts, the privacy of iPhone owners is in the hands of app developers and data companies. Given their history, trusting them with our personal information is a lot to ask.