Cybercrime is a business and a lucrative one at that. We hear about organisations being robbed and blackmailed, oftentimes for millions of dollars, pounds and crypto currencies. Somewhere, you can bet, somebody is reclining in a sports car, swilling cognac, puffing on a cigar and celebrating the lifestyle on Instagram.

As such, it can – if you’re very lucky – be revealing to ask cybersecurity professionals how they’d make their fortunes should they wake up one morning and decide to change sides. How, knowing what they know, would they make their first crypto currency million and buy a first Bentley?

But, not in this case. ‘You’ll have to sign an NDA,’ says Professor Ali Al-Sherbaz FBCS. Smiling, Dr Qublai Ali-Mirza says: ‘You can’t quote me.’

Both work for the University of Gloucestershire, where Sherbaz is an associate professor and academic subject leader in technical and applied computing. Ali-Mirza is a course leader in cybersecurity.

Grudging respect from reverse engineering

So, which piece of malware did the pair find most fascinating? Whose tradecraft do they admire most?

‘Zeus,’ says Ali-Mirza emphatically. ‘It was first identified in 2007. It couldn’t be spotted. It worked under the radar for two years and, the records show, it stole more the one hundred million dollars but, I’m sure it stole more than that.’

Zeus was a trojan horse which ran on Windows systems. Though it was used to carry out many malicious attacks, it gained infamy as a means of stealing banking information by grabbing, keylogging and manipulating browser traffic. It was spread mainly by phishing and drive-by downloading. Zeus’ superpower was its ability to remain undetected. Many of the best contemporary anti-virus programmes were stumped by its stealth techniques.

‘It was really cleverly designed,’ says Qublai. ‘I’ve analysed Zeus and variants of it myself. The way it was programmed was really good. By that I mean it propagated really efficiently and, while it was spreading, it was morphing into something else. As it moved forward, it changed its [file] signatures and its heuristics – its behaviour. And, it was deleting the previous versions of itself. It was very biological...’

For his money, Al-Sherbaz says Chernobyl remains a piece of malware worth remembering – for many of the wrong reasons. This virus emerged in 1998 and went on to infect nearly 60 million computers across the globe.

Chernobyl’s payloads were highly destructive. If your system was vulnerable, the virus could overwrite critical sectors on the hard disk and attack the PC’s BIOS. Damage these and the computer is rendered inoperable.

‘Zeus though, it was really intelligent,’ Al-Sherbaz says, agreeing with his colleague. ‘The groups, I think, understand how real biological viruses work. They recruited smart people. I’m really interested in how they recruit people. These aren’t just people who do coding. I’m sure they must have a recruitment process and get people from different backgrounds – cryptanalysts… biologists… network security experts. It was impressive.’

Yesterday’s troubles and today’s

Wind the clock forward to today and we’re still seeing malware that can evade detection and, ultimately, avoid anti-virus software. Today’s top AV programmes promise isolation, removal, real-time blocking, detection, response, behaviour-based monitoring and remediation. The list goes on. Despite all this and decades of product development, we’re still vulnerable to malware. Why?

‘It’s a good question,’ says Dr Ali-Mirza. ‘Your antimalware software is consuming resources and you’re still vulnerable. The answer is simple. Though the industry is advanced, there’s a lack of intelligence sharing. It’s about business. A lot of the tools and techniques are proprietary and [firms] don’t share the intelligence among themselves. A lot of organisations are quite closed off, they don’t share their techniques. They take pride in this, saying: “Our database of malware signatures is better than x, y, z’s”.’

This approach can afford vendors a marketing advantage. It will enable them to sell their products based on the richness of their database of known virus signatures. It doesn’t, however, afford vendors a technical advantage.

‘Vendors might say, “We are the first people to identify this piece of malware. If you buy our product, you are more secure”,’ Dr Ali-Mirza explains. ‘The problem is, identifying just a signature… just a heuristic feature... just a piece of malware – it isn’t enough. Malware becomes lethal based on the vulnerability it is exploiting. When a zero-day attack is identified and exploited, that’s the most lethal thing in this industry.”

Criminals have unfair advantages

The playing field where attack and defence happen isn’t level. The pair of security academics were quick to point out that those who work on the right side of the law are bound by some significant restrictions.

Firstly, malware itself isn’t bound or limited by any legislation: criminals can use any tool and any technique. Ali-Mirza says: ‘They can pick up any open source tool, further enhance it and use it as an attack.

‘Hackers are getting more innovative too,’ he continues. ‘But, more importantly, criminals only have to get it right once. Security, by contrast, is a consistent exercise which needs to evolve.’

Echoing this point, Professor Ali Al-Sherbaz explains that, in his opinion, criminals have another huge advantage: they have, to a degree, the luxury of time. When it comes to designing and deploying their software, they can plan, test, iterate and, finally, attack their chosen flaw. Defenders, however, might only have moments to react when they notice a vulnerability being exploited.

Dissecting ransomware

Of all the types and families of malware which do daily damage online, ransomware is the kind which steals most headlines. From Wannacry to the Colonial Pipeline attack, to JBS foods and CAN Financial, ransomware attacks have caused havoc.

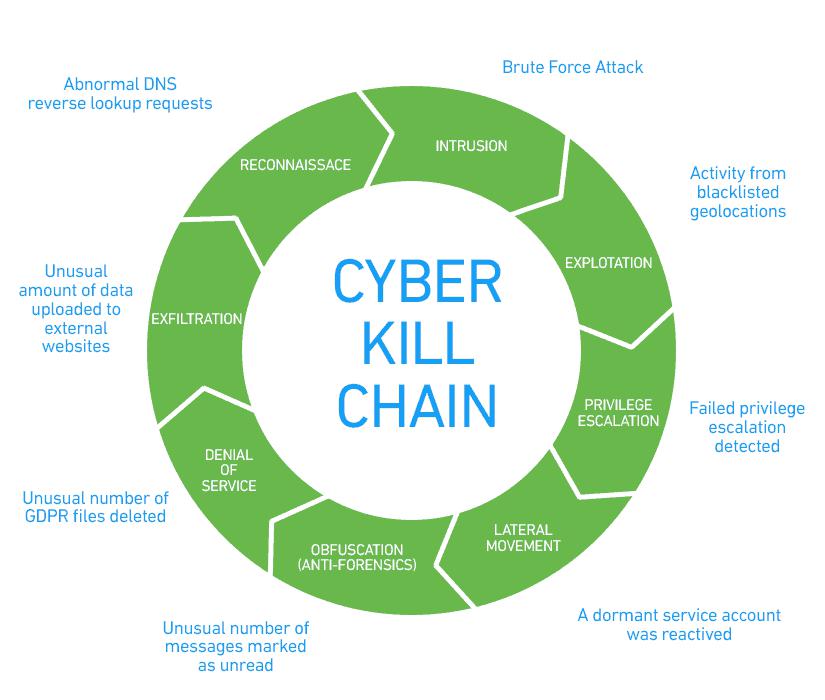

It’s against this backdrop that Dr Ali Mirza and four others from the School of Computing and Engineering at the University of Gloucester published the paper: Ransomware Analysis using Cyber Kill Chain.