Get important education news and analysis delivered straight to your inbox

More and more jobs require training in science, technology, engineering and math. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, occupations in these fields are projected to grow 8 percent by 2029, more than double the growth rate of non-scientific professions. There’s a pressing need to attract young students from all backgrounds to study these fields in college.

One large group trailing behind are rural and small town students, who account for 3 out of 10 students nationally. A new analysis of federal data finds that only 13 percent of rural and small town students major in math and science in college, compared with almost 17 percent of students in the suburbs. That’s a large 4 percentage point gap. Urban students also trail suburban students when it comes to studying science, but only by a little, according to the federal data.

Fewer rural and small town students go to four-year colleges and that explains part of this gap. But even rural and small town students who do go to four-year colleges are less likely to major in science or math.

It’s curious that rural students aren’t pursuing science in greater numbers. Many rural towns rely on science-heavy fields, from agriculture and mining to forestry and manufacturing. Scholars are trying to understand why more rural students don’t pursue studies that could lead to well-paying careers for themselves and a more productive economic future for their communities.

Some of the clues are contained in this June 2021 data analysis conducted by two researchers at Claremont Graduate University and Indiana University. They scrutinized a large federal dataset of more than 20,000 students across the nation who started high school in 2009 and were surveyed through to their third year of college in 2016. The students in the survey were specially selected to represent the nation and rural, suburban and city students each made up about a third of the students. (There are two different categories for non-urban students in the federal data: rural and small town. Rural accounts for about 20 percent of U.S. students. Small towns, also far from major metropolitan areas, account for another 10 percent of students. Many small towns started as market towns or as small manufacturing towns in the industrial era and are now economically struggling. One example is Harlan, Kentucky, a former coal town. Others, like Provincetown, Massachusetts, are seasonal tourist towns. See map at the top of this page.)

The demographics of rural and small town students are distinctive. Two-thirds of these students are white, a much higher percentage than either suburban or city students. Their families also tend to be poorer and less educated, particularly so for the students in economically distressed small towns.

Rural students began high school with the same interest in science and math careers as their suburban counterparts, the survey reveals. At the start of ninth grade, almost 12 percent of both groups of students said they hoped to have a career in life and physical sciences, engineering, mathematics, architecture, or information technology industries.

However, there are also warning signs that many of these rural students aren’t as well prepared for this pathway. Rural students posted lower scores on math assessments in early ninth grade than their suburban counterparts and they had taken half as many high-school level courses in middle school.

By the end of 11th grade, rural students’ desire to pursue a career in math or science dropped below 9 percent. Some suburban students became disenchanted with a life in math or science too, but their enthusiasm fell only 1 percentage point. At the same time, the math achievement gap between rural and suburban students grew even larger.

The researchers point to three explanations for the rural shift away from science: classes, teachers and extracurricular activities.

Rural and small town schools are far less likely to offer advanced math and science courses, such as Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate classes. For example, 63 percent of rural students had access to an in-person calculus class at their school compared with 83 percent of suburban students. In many cases, students who want to take an advanced class that isn’t offered can take an online version. In theory, these remote classes can prepare students for challenging college programs in, say, engineering. But Guan Saw, an associate professor at Claremont and one of the co-authors, points out that students often miss out on forming a relationship with a good teacher at their high school who can inspire a student to make the decision to major in engineering in the first place.

Teacher quality is another impediment. In the survey data, researchers discovered that rural math and science teachers didn’t participate in professional development as often or feel as confident in their teaching ability or subject knowledge as suburban math and science teachers. “Even when rural students have access to the same coursework, they are not taught by highly qualified teachers,” said Saw.

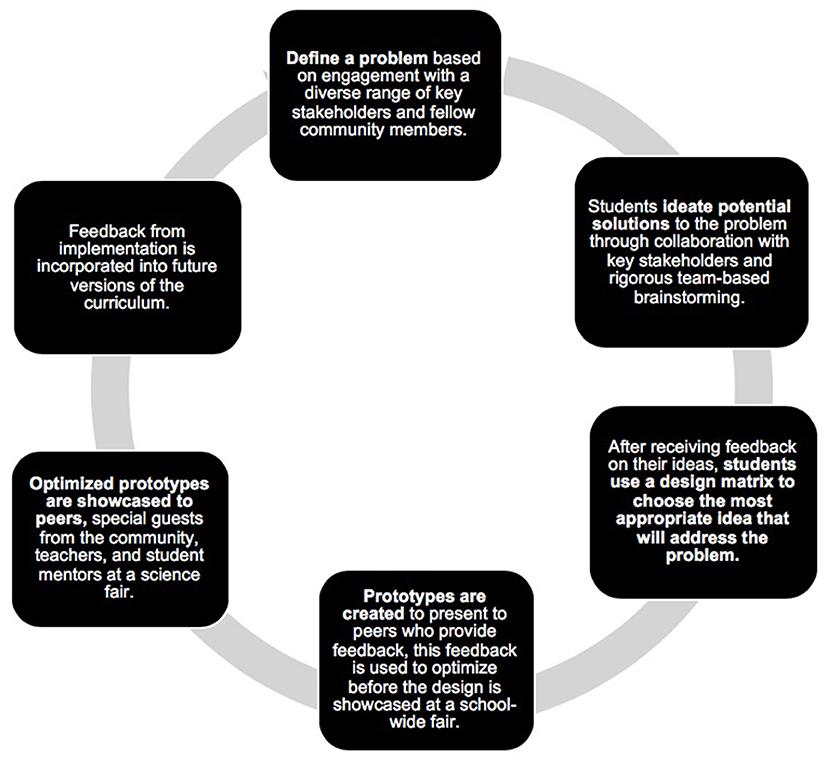

Rural students also had fewer opportunities to do math and science outside of the classroom, activities such as science fairs, robotics competitions and math clubs. Sometimes these out-of-school projects and social experiences can motivate students more than performing well in a science or math class.

Solving these problems won’t be easy. The Rural STEM Education Act proposes to improve teacher training and increase both online and hands-on science education in rural schools. It has bipartisan support, has passed the House and may become law. But it will remain hard to justify hiring an Advanced Placement physics teacher for just a handful of students in a small school and harder to recruit an excellent teacher to teach it.

There are many studies about the dearth of Black and Latino college students who pursue science but rural students, who are predominantly white, are another underrepresented group. Getting more of them to study science may not only help improve their lives but could also help revitalize economically distressed areas of our country. That’s something that could benefit all of us.

This story about rural science was written by Jill Barshay and produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

The Hechinger Report provides in-depth, fact-based, unbiased reporting on education that is free to all readers. But that doesn't mean it's free to produce. Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Join us today.