For scientists developing new drugs, it’s hard to go wrong targeting a family of receptors that regulate virtually every known process in human beings. G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are found throughout the body, and research into their roles has yielded an estimated 700 FDA-approved drugs so far. But that productivity comes with a problem. With so many molecules already targeting these receptors, it’s harder for scientists to find new ways and new places to hit them.

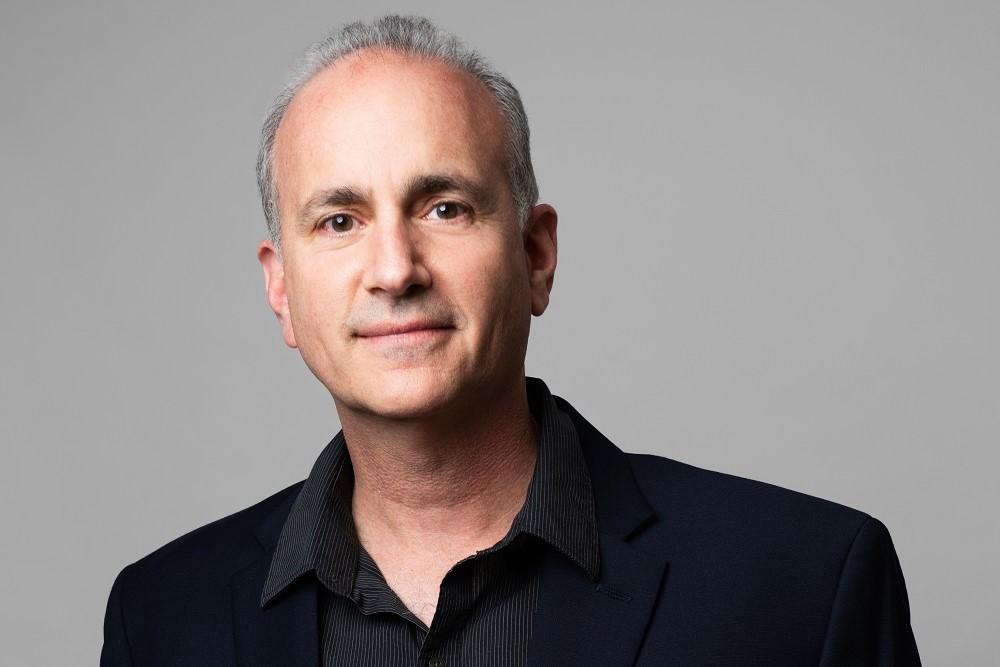

Robert Lefkowitz, who was awarded the 2012 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his GPCR discoveries, has developed new techniques to study these receptors and identify molecules that bind to them in ways drugs haven’t before. That research forms the basis of South San Francisco-based Septerna, a new biotechnology company launching Thursday backed by a $100 million Series A round of funding led by Third Rock Ventures.

There are about 800 GPCRs in the human genome. Scientists started learning about them in the early 1970s. Lefkowitz was one of the field’s pioneers, conducting research into the nature and function of these receptors. GPCRs play a huge role in the way we taste and the way we smell, Lefkowitz said. If you’re taking something for winter sniffles right now, chances are good it’s a drug that targets a GPCR. However, while scientists have found ways to drug many of these receptors, hundreds more have yet to be targeted.

Lefkowitz, a Duke University professor of medicine, biochemistry, and chemistry, and a Septerna co-founder, was not looking for new ways to drug GPCRs. Instead, his research focused on finding new ways to study them. His Duke lab developed techniques to isolate the receptors and study them outside of a cell, but in a way that also mimics the processes and circumstances that they would encounter, such as their interactions with molecules. Some of the post-doctoral researchers in Lefkowitz’s lab who helped develop these technologies tried to convince him to seek funding to start a company. By his own admission, he did not embrace that idea. As an academic, Lefkowitz said he thought it best to stay in that silo. A phone call from a venture capitalist changed his mind.

Jeff Finer, a Third Rock venture partner who is now also Septerna’s CEO, knew Lefkowitz, having met him a decade ago when Finer worked at another biotech company. About three years ago, Finer said he called the Duke scientist to get his thoughts on the GPCR field. At the time, Lefkowitz’s lab had been publishing its research while the post-docs continued to mull the idea of forming a company. Finer’s call kicked that plan into motion. He proposed combining the Lefkowitz lab techniques with computational technologies to fuel drug discovery. The Septerna technology platform is called Native Complex. In addition to isolating GPCRs, the technology screens libraries of molecules to find the ones that can bind to the receptors.

“By having it out of a cell now, we can do a number of things that were impossible before,” Finer said. “It opens a toolbox of drug discovery technology not applicable to this class before. We can screen literally billions of compounds and find which ones stick to receptors in different ways.”

GPCRs lend themselves to binding to small molecules, making them very “druggable.” But currently available drugs connect to these receptors at known binding sites. In biotech parlance, these sites are orthosteric. Native Complex finds other places on a receptor where a small molecule can bind to confer their therapeutic effects. These alternative sites are allosteric. By identifying allosteric sites on GPCRs, the real estate available to small molecules becomes much larger, Lefkowitz said.

Septerna’s approach goes beyond finding new binding locations for small molecules. The conventional thinking about GPCRs is that these receptors are like on/off switches—drugs that bind to them either block the receptor or activate it, Lefkowitz said. But binding to allosteric sites offers the potential to offer a tunable effect, like adjusting a rheostat.

Finer said Septerna will use its approach to go after GPCRs that have been considered undruggable or difficult to drug. In the cases where a GPCR is already addressed by a peptide or biologic drug, the biotech may look for a way to hit that target with small molecules. In other cases where there is already a small molecule drug for a GPCR, Septerna may look for a way to drug that target with a different mechanism of action. To start, Septerna has five programs spanning four therapeutic areas: endocrinology, central nervous system, metabolic disease, and inflammation. The goal is to get three of those programs to yield Phase 1-ready drug candidates “in a couple of years,” Finer said.

There are other biotechs pursuing new GPCR drugs. Longboard Pharmaceuticals, a spinout of Arena Pharmaceuticals, is developing GPCR drugs for neuroscience indications. Longboard went public last year, raising $80 million. ShouTi is bringing computational approaches to its GPCR drug hunt using technology of its co-founder, the drug research software company Schrodinger. ShouTi unveiled its own $100 million financing, a Series B round, last October.

Besides Third Rock, the other investors in Septerna’s Series A round include Samsara BioCapital, BVF Partners, Invus Financial Advisors, Catalio Capital Management, Casdin Capital and Logos Capital. Finer acknowledged that Septerna’s financing is larger than the typical Series A round of a Third Rock-backed company. But he noted that the startup’s pipeline is more advanced, and the company will be working on multiple programs in parallel. To support those programs, Septerna will expand its headcount, which Finer projects will more than double to 40 to 50 employees this year.

“While it is a Series A, we think it’s the right amount of money to get us to the point where we can advance all the parts of our pipeline,” Finer said. “We have so many great opportunities, we don’t want to leave any of them behind.”

Photo by Septerna

Promoted

Bill Martin, the Global Therapeutic Area Head of Neuroscience at The Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson, shared some of the promising developments in the neuroscience space, such as the rise of neuro-immunology and the industry’s embrace of digital health tools to support drug development in a recent interview.

Stephanie Baum

Promoted

The report, Resilience in volatility: Modernizing the supply chain, highlights three areas that Fortune 500 and mid-size companies need to address to implement technology such as machine learning, cloud computing and risk management tools to improve production and delivery.

MedCity News and Microsoft