By William Choong, Hoang Thi Ha, Le Hong Hiep and Ian Storey*

INTRODUCTION

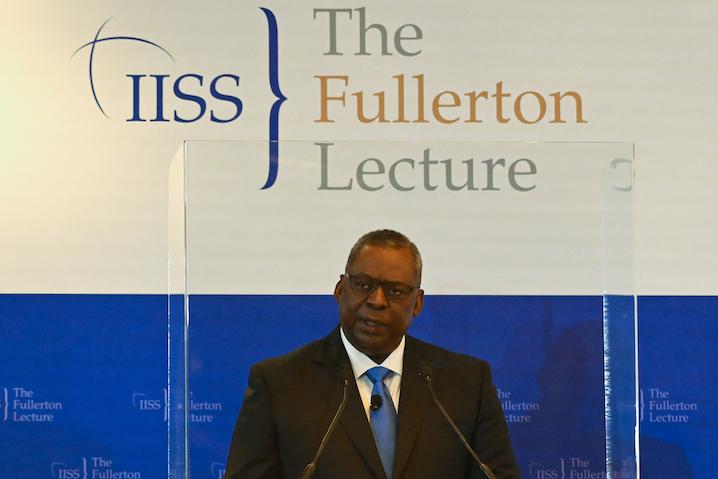

US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin’s swing through Southeast Asia on 26-29 July, during which he visited Singapore, Vietnam and the Philippines, was significant because it was the first trip to the region by a US cabinet-ranking member since President Joseph Biden took office in January.

The first six months of the Biden administration had been largely focused on rebuilding US relationships with high-priority allies and partners in Northeast Asia (Japan and the Republic of Korea), Europe (NATO and the G7) and the Quad (especially India) as well as setting the parameters of engagement with China – America’s key strategic competitor. In contrast, President Biden has not had a single telephone call with any Southeast Asian leader. The administration’s belated outreach to Southeast Asia led to concerns that Washington was neglecting the region at a time when China’s regional influence continued to expand through extended trade and investment ties, vaccine assistance and in-person diplomacy.[1]

Against this backdrop, the significance of Austin’s trip goes beyond issues of defence cooperation. As he highlighted in his Fullerton Lecture in Singapore, the principal objective of his trip was “to reaffirm enduring American commitments” to Southeast Asia.[2] This

Perspective

examines the outcomes and messages from Austin’s trip, and gauges the broad contours of the Biden administration’s Southeast Asia policy within its broader Indo-Pacific strategy.

AUSTIN’S FULLERTON LECTURE: REVERTING TO FORM

Austin’s Fullerton Lecture in Singapore, organised by the London-based International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), can be seen as the first Southeast Asia policy speech by the Biden administration. As indicated in its title – “The Imperative of Partnership” – the lecture reaffirmed the importance of alliances and partnerships, the lodestone of America’s Asia policy, which had been undermined by the Trump administration’s transactional and unilateral approach. Austin’s statement that the US would move in “lockstep” with its allies and partners on a range of issues[3] such as the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, coercion from rising powers, North Korea’s nuclear arsenal and the Myanmar crisis, reflects the Biden administration’s internationalist approach in addressing common global challenges – a clear departure from the Trump administration.

The Fullerton Lecture went beyond the defence-security domain and offered tangible US deliverables to the region. This message was aptly calibrated for his Southeast Asian audience, many of whom prefer to see America providing a positive agenda of regional cooperation rather than a zero-sum narrative of US-China rivalry. Austin hit the right note in saying that America’s enduring ties in Southeast Asia “are bigger than just geopolitics”.[4]

He emphasised US pandemic assistance, especially the donation of 40 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines throughout the Indo-Pacific, including Indonesia, Laos, the Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam. Taking an indirect swipe at China-whose vaccines are mainly sold and have relatively lower efficacy rates-Austin praised US-developed vaccines as “medical miracles” that are “incredibly effective at saving lives and preventing serious illness” and that were being donated with no conditions or strings attached.[5] Austin’s statement mirrors what Kurt Campbell, the Biden Administration’s Indo-Pacific czar, had said earlier in July. Speaking to the Asia Society, Campbell said that the US needed to “do more” in Southeast Asia and he expected “exciting” and “decisive” announcements on vaccine diplomacy and infrastructure when the Quad leaders meet in Washington in late 2021.[6]

When addressing the challenges posed by China, Austin also sought to strike the right notes with his Southeast Asian audience who are concerned that too strident a push by Washington against China would pressure regional states into making invidious choices between the two powers.[7] While criticising Chinese behaviour on a range of issues from the South China Sea dispute and tensions with Taiwan and India, to actions against Uighur Muslims in Xinjiang, Austin also gave assurances that Washington was “committed to pursuing a constructive, stable relationship with China, including stronger crisis communications” and is “not asking countries in the region to choose between the US and China”. In a post-event roundtable discussion organised by the IISS, many regional analysts thought that this message on China was “about right”.[8] This view, however, was not shared by China. In its remarks on 29 July, the Chinese Embassy in Singapore harshly criticised Austin’s lecture, saying that he had “played up the so-called China threat in an attempt to drive a wedge between China and its neighbors”.[9] Beijing has consistently used this narrative in its contest for influence with the US in the region.

Austin’s lecture reiterated US support for ASEAN’s central role in the region. It is noteworthy that Austin went so far as to “applaud ASEAN for its efforts to end the tragic violence in Myanmar” even though the group has been criticised for its delayed appointment of a special envoy to Myanmar. Arguably, this support is not based on high expectations of what ASEAN can do, and is instead a pragmatic consideration given the lack of better alternatives due to Washington’s limited leverage over, and peripheral interests in, the Myanmar situation.

Austin also stressed that the Quad sought to complement – not replace – ASEAN-led mechanisms, including the ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting-Plus (ADMM-Plus). However, whether Southeast Asians have been reassured by this message remains to be seen. Washington realises the importance of reassuring the region about ASEAN centrality even as the US continues to further its investment in the Quad for the desired strategic-security outcomes which it does not expect ASEAN to be able to provide.

SINGAPORE: CONSOLIDATING STRATEGIC TIES

Austin’s visit to Singapore underscored the strategic importance that the Biden administration attaches to Singapore – a strong supporter of the US security presence in the region, including through logistical support for US military aircraft and vessels, and facilitation of the “regular rotational deployment” of US Littoral Combat Ships and P-8 Poseidon aircraft. As noted in the Joint Statement between Austin and his Singaporean counterpart Dr Ng Eng Hen, “[t]his support is anchored on the shared belief that the US’ presence in the region is vital for its peace, prosperity, and stability”.[10] On its part, the US is a longstanding supporter of Singapore’s overseas training and exercises, and will be hosting Singapore’s future F-35B fighter aircraft detachment.[11]

The longstanding and multi-faceted US-Singapore defence relationship was reaffirmed by the 2019 signing of the Protocol of Amendment which renewed the 1990 Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) regarding America’s use of facilities in Singapore and extended the MOU by 15 years, and another MOU on the establishment of a Republic of Singapore Air Force fighter training detachment in the US-territory of Guam.

During Austin’s visit, both sides highlighted new areas of bilateral defence cooperation, especially in cyber defence and strategic communications.[12] These include Singapore’s establishment of the multilateral Counter-Terrorism Information Facility in which the US is a partner country. Singapore also joined the multi-national Artificial Intelligence Partnership for Defence in May 2021. The partnership seeks to enable multilateral cooperation and exchange of best practices on “responsible AI” in the defence sector.[13]

Apart from Austin’s visit, Washington has injected fresh energy into the bilateral relationship. Before him, the outgoing commander of the US Indo-Pacific Command, Admiral Philip S. Davidson, and his successor, Admiral John Aquilino, visited the city-state in April and July, respectively. On 29 July, the Biden administration announced the nomination of entrepreneur Eric Kaplan as Washington’s new ambassador to Singapore, a post which had been left vacant since January 2017. A day later, the White House announced that US Vice-President Kamala Harris would visit Singapore and Vietnam in August to strengthen relationships and expand economic cooperation with America’s two “critical Indo-Pacific partners”.[14] Washington has good reasons to up its game in Singapore beyond defence matters to win the hearts and minds of Singaporeans, many of whom have cultural and familial bonds with China. A Pew Research Centre report in July 2021 showed that 64 per cent of Singaporeans polled had a favourable view of China – the highest among the 17 countries surveyed.[15]

VIETNAM: ADDRESSING THE PAST, LOOKING TO THE FUTURE

Austin’s visit to Vietnam was the latest in a series of US diplomatic overtures to the country in recent months. In July, Vietnam received a second ex-US Coast Guard cutter donated by the United States. Following a Vietnam-US agreement to address US concerns about Vietnam’s currency practices on 19 July 2021,[16] the Office of the US Trade Representative formally closed a Section 301 investigation into this matter, removing a major source of contention in bilateral relations.[17] By early August, the US had donated five million doses of the Moderna vaccine against COVID-19 to Vietnam through the COVAX Facility, making Vietnam one of the largest beneficiaries of Washington’s “vaccine diplomacy”. Secretary Austin’s visit was part of America’s coordinated efforts to deepen ties with Vietnam to win Hanoi’s support for its regional strategic agenda.

Austin’s meetings with President Nguyen Xuan Phuc and Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh in Hanoi focused on bilateral cooperation to fight the COVID-19 pandemic, which is currently Vietnam’s most immediate concern. The Vietnamese hosts expressed their appreciation for America’s unconditional vaccine donations. During Austin’s meeting with Vietnamese Defence Minister Phan Van Giang, they discussed measures to further promote cooperation in line with the 2011 MOU on defence cooperation and the 2015 Joint Vision Statement on defence relations. Priority areas of cooperation include addressing legacy issues from the Vietnam War, maritime law enforcement capacity building, military medicine cooperation, training and defence industry collaboration.

A highlight of the visit was the signing of an MOU under which the US, through the participation of Harvard and Texas Tech University, will help Vietnam locate, identify and recover the remains of hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese soldiers killed during the Vietnam War but who are still listed as missing in action (MIA).[18] This move will contribute to the building of mutual trust as the MIA issue still carries great emotional significance for the Vietnamese people. Helping Vietnam solve this legacy issue will remove an obstacle of strong political symbolism to bilateral defence ties, paving the way for stronger and more substantive defence cooperation between the two former foes in the future.

Before Austin left for Southeast Asia, there were rumours that the two sides might also sign a General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA). GSOMIAs set the legal framework for parties to establish terms for the protection and handling of classified military information exchanged between them. The signing of such an agreement would signify a meaningful step towards more substantive defence cooperation between the US and Vietnam, and facilitate bilateral coordination on issues of mutual concern, including the South China Sea dispute. The two sides are said to have been in talks about the agreement for several years. However, media reports on the outcomes of Austin’s visit did not mention the signing of a GSOMIA. It is unclear if the signing of a GSOMIA has been delayed, or if the agreement has been signed but both sides decided not to publicise it.

As noted earlier, Vice President Kamala Harris is scheduled to visit Vietnam in August, the first sitting US Vice President to do so. Further meetings between the two countries’ leaders, including at the highest level, should also be expected as they seek further measures to strengthen their bilateral relations, including military ties in particular.

Faced with unprecedented security challenges caused by the rise of China and its growing assertiveness, the US and Vietnam have recently found strong incentives to work together to build a more resilient and substantive bilateral relationship. Austin’s visit will strengthen bilateral relations in that direction and facilitate their potential upgrade to the level of strategic partnership in the future.

THE PHILIPPINES: MOVING THE ALLIANCE FORWARD

The third and final leg of Austin’s Southeast Asian trip was arguably the most successful in that it helped put the US-Philippines alliance back on track after more than a year of uncertainty. That uncertainty had arisen from President Rodrigo Duterte’s threat to terminate the 1999 US-Philippines Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA) which provides the legal framework for the US military to undertake training activities in the Philippines with the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP). Without the VFA, the 1951 Mutual Defense Treaty (MDT

) and the 2014 Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) that allows the US to preposition military equipment at various AFP bases, cannot function effectively.In February 2020, Duterte had served notice that the Philippines would withdraw from the VFA after 180 days. The proximate cause was the US State Department’s denial of a travel visa to one of Duterte’s political associates who had helped execute his “war on drugs”. The move was also in keeping with Duterte’s pledge to “divorce” the US and pursue a more balanced foreign policy. Further, Duterte may have calculated that by threatening to abrogate the VFA, the US would hold off criticism of his administration’s human rights record. Some Philippine politicians had also long grumbled that the VFA prevented the legal prosecution of US service personnel who had committed serious crimes in the Philippines.

However, the Philippines’ national security establishment lobbied hard to keep the VFA. The US-Philippine alliance strengthens Manila’s hand in its maritime territorial and jurisdictional dispute with Beijing in the South China Sea: it provides the AFP with a security guarantee that if they are attacked, US forces would provide support as well as valuable training opportunities and millions of dollars in military assistance every year. Duterte’s threat to abrogate the VFA had made long-term planning for the alliance almost impossible, causing great frustration in both the Trump and Biden administrations.

As a result of this lobbying, Duterte suspended the abrogation of the VFA three times: in June and November 2020 and in June 2021. Between February and May 2021, US and Philippine officials had negotiated an addendum to the VFA. Although the details of that addendum have not been released, Philippine Ambassador to the US, Jose Manuel Romualdez, indicated that it had improved the terms of the VFA, presumably meaning it had addressed Philippine concerns regarding the prosecution of US service personnel.[19] In June, Duterte promised he would study the revised agreement. The third extension would have kept the VFA alive until February 2022, and many observers expected that Duterte would agree to a further postponement early next year and leave the final decision to his successor (constitutionally Philippine presidents are limited to one six-year term and Duterte will leave office in June 2022).

However, in a 75-minute meeting with Austin, Duterte agreed to withdraw the letter of termination. The decision was announced the next day at a joint press conference with Austin and his Philippine counterpart Delfin Lorenzana.[20] Lorenzana said he did not know why Duterte had changed his mind. However, increased tensions with China in the South China Sea – including the presence of hundreds of Chinese fishing boats at Whitsun Reef in the Philippines’ EEZ in March-April[21] – were almost certainly a factor in the President’s calculations. Duterte’s spokesperson, Harry Roque, said the decision was based on “upholding the Philippines’ strategic core interests ... and clarity of US position on its obligations and commitments under the MDT”.[22] After Austin had departed Manila, Duterte himself said he had withdrawn his opposition to the VFA as a quid pro quo for America’s donation of more than six million doses of Johnson & Johnson and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines to the Philippines.[23]

Prior to Austin’s visit, there had been some signs of progress in US-Philippine relations. In January, the US had reiterated its commitment to come to the aid of the Philippines if it were attacked in the South China Sea.[24] In April, the annual

Balikatan

bilateral military exercise took place[25] (the drills in 2020 were cancelled due to the pandemic), and in June, the US State Department approved in principle the sale of F-16 fighter jets to the Philippines.[26] (Manila is nevertheless still looking at alternative options).

But since Duterte took office in 2016, the US-Philippine alliance has been treading water, and given the President’s continued animus towards America, it is still possible that he could reverse his decision on the VFA, or impede negotiations between the two sides on improving military cooperation. As such, real progress on strengthening the US-Philippines alliance – such as negotiating a GSOMIA, designing new combined exercises and implementing EDCA – will have to wait until Duterte’s successor takes office in June 2022.

CONCLUSION

Austin’s swing through Southeast Asia was positively received by the security establishments in the host countries.[27] His trip reflects Washington’s growing cognizance of the need to intensify diplomatic engagement with Southeast Asia – “the fulcrum of the Indo-Pacific region” where the US holds “enduring interests”, as affirmed in the Southeast Asia Strategy Act.[28] The Act, which was passed by the US House of Representatives in April, also requires a comprehensive strategy for engaging Southeast Asia across multiple dimensions, from trade and investment flows to diplomatic and security arrangements. The Biden administration has thus far taken only some initial steps towards this end.

Austin’s Southeast Asia tour is part of the Biden administration’s “charm offensive” towards the region after the first six months of lacklustre interactions. His message of US commitment to “deepen and expand Southeast Asian alliances, partnerships and multilateral engagements”[29] will be echoed by Secretary of State Antony Blinken when he meets ASEAN foreign ministers in early August. US Vice-President Kamala Harris will also visit Singapore and Vietnam this month. Kurt Campbell has hinted that a special ASEAN-US Summit is being considered, and another visit by US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken might be on the cards.[30]

Given the growing significance of Southeast Asia – be it as a key arena of US-China strategic competition or a growing source of US prosperity – it is in America’s interests to build upon this momentum to deepen its engagement with the region in a sustained and comprehensive manner.

*About the authors: William Choong, Le Hong Hiep and Ian Storey are Senior Fellows and Hoang Thi Ha is Fellow and Co-coordinator of the Regional Strategic and Political Studies Programme at the ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute.

Source: This article was published in

ISEAS Perspective 2021/103

ENDNOTES

[1] See Colum Lynch, Jack Detsch, and Robbie Gramer, “The Glitch That Ruined Blinken’s ASEAN Debut”,

Foreign Policy,

27 May 2021,

https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/05/27/blinken-asean-meeting-pivot-asia-middle-east

; James Crabtree, “A Confused Biden Team Risks Losing Southeast Asia”,

Foreign Policy,

27 June 2021,

https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/06/27/southeast-asia-asean-china-us-biden-blinken-confusion-geopolitics

; Hoang Thi Ha, “Beijing’s head start over Biden in South-east Asia”,

Straits Times

, 31 May 2021,

https://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/beijings-head-start-over-biden-in-south-east-asia

.

[2] Secretary of Defense Remarks at the 40th International Institute for Strategic Studies Fullerton Lecture (As Prepared), US Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III, 27 July 2021,

https://www.defense.gov/Newsroom/Speeches/Speech/Article/2708192/secretary-of-defense-remarks-at-the-40th-international-institute-for-strategic

.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ken Moriyasu, “US does not support Taiwan independence: Kurt Campbell”,

Nikkei Asia

, 7 July 2021,

https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Biden-s-Asia-policy/US-does-not-support-Taiwan-independence-Kurt-Campbell

.

[7] William Choong, “The United States’ ‘Mini’ Shangri-La Dialogue: Stand and Deliver”,

Fulcrum,

27 July 2021,

https://fulcrum.sg/the-united-states-mini-shangri-la-dialogue-stand-and-deliver

.

[8] IISS post-event discussion on Austin’s Fullerton Lecture, 27 July 2021, attended by one of the authors.

[9] Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Republic of Singapore, “Remarks of the Spokesperson of the Chinese Embassy in Singapore in Response to U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd James Austin III’s China-Related Remarks at the Fullerton Lecture”, 29 July 2021,

http://www.chinaembassy.org.sg/eng/sgsd/t1895923.htm

.

[10] Joint Statement by United States Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III and Singapore Minister for Defence Dr Ng Eng Hen,

https://www.mindef.gov.sg/web/portal/mindef/news-and-events/latest-releases/article-detail/2021/July/27jul21_fs

.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Nirmal Ghosh, “US Vice-President Kamala Harris to visit Singapore and Vietnam”,

The Straits Times,

30 July 2021,

https://www.straitstimes.com/world/united-states/us-vice-president-kamala-harris-to-visit-singapore-and-vietnam

.

[15] Laura Silver, “China’s international image remains broadly negative as views of the U.S. rebound”, Pew Research Center, 30 June 20211,

https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/06/30/chinas-international-image-remains-broadly-negative-as-views-of-the-u-s-rebound

.

[16] US Department of the Treasury, “Joint Statement from the U.S. Department of the Treasury and the State Bank of Vietnam”, 19 July 2021,

https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0280

.

[17] Office of the US Trade Representative, “USTR Releases Determination on Action and Ongoing Monitoring Following U.S.-Vietnam Agreement on Vietnam’s Currency Practice”, 23 July 2021,

https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/press-releases/2021/july/ustr-releases-determination-action-and-ongoing-monitoring-following-us-vietnam-agreement-vietnams

.

[18] For an analysis of the significance of the signing of the MOU, see Le Hong Hiep, “Secretary Austin’s Visit to Vietnam: Building Trust to Strengthen Defence Ties”,

Fulcrum,

28 July 2021,

https://fulcrum.sg/secretary-austins-visit-to-vietnam-building-trust-to-strengthen-defence-ties

.

[19] Karen Lema, “Philippine envoy confident Duterte will back revamped U.S. defence pact”, Reuters, 3 June 2021,

https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/philippine-envoy-confident-duterte-will-back-revamped-us-defence-pact-2021-06-03

[20] Frances Mangosing, “Lorenzana: ‘VFA in full force again’”,

Philippine Daily Inquirer

, 30 July 2021,

https://globalnation.inquirer.net/198126/duterte-recalls-decision-to-junk-vfa-after-meeting-with-top-us-official

[21] Laura Zhou, “South China Sea: Chinese boats keep up steady presence at disputed Whitsun Reef, says US ship tracker”,

South China Morning Post

, 22 April 2021,

https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3130676/china-present-whitsun-reef-and-surrounds-2019-says-us-group

.

[22] Idrees Ali and Karen Lima, “Philippines’ Duterte fully restores key US troop pact”, Reuters, 30 July 2021,

https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/us-aims-shore-up-philippine-ties-troop-pact-future-lingers-2021-07-29

.

[23] Genalyn Kabiling, “‘Give and take’: VFA retention a ‘concession’ after US vaccine donation, Duterte admits”,

Manila Bulletin

, 3 August 2021,

https://mb.com.ph/2021/08/03/give-and-take-vfa-retention-a-concession-after-us-vaccine-donation-duterte-admits

[24] Wendy Wu and Teddy Ng, “China-US tension: Biden administration pledges to back Japan and Philippines in maritime disputes”,

South China Morning Post

, 28 January 2021,

https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3119578/south-china-sea-blinken-pledges-us-backing-philippines-event

.

[25] “US and Philippine Forces Conclude 36

th

Balikatan Exercise”, US Embassy in the Philippines, 23 April 2021,

https://ph.usembassy.gov/us-and-philippine-forces-conclude-36th-balikatan-exercise

.

[26] “US State Dept OKs possible sale of F-16s, missiles to Philippines”, Reuters, 25 June 2021,

https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/us-state-dept-approves-possible-sale-f-16-fighters-missiles-philippines-pentagon-2021-06-24

.

[27] The IISS post-event discussion on Austin’s Fullerton Lecture, 27 July 2021; Authors’ interviews with a number of Southeast Asian states’ officials; and podcast on 49

th

Fullerton Lecture: US Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin,

IISS Sounds Strategic

, 29 July 2021,

https://www.iiss.org/blogs/podcast/2021/07/40th-fullerton-lecture-us-secretary-of-defense-austin

.

[28] H.R.1083 – Southeast Asia Strategy Act, US Congress,

https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1083

.

[29] Ibid.

[30] James Crabtree, “What does it mean to be America’s partner?”,

Straits Times

, 24 July 2021,

https://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/what-does-it-mean-to-be-americas-partner-0

.