Photo: Erik Fok

Despite the prevalence of satellite data, traditional map-makers continue to tell remarkable stories with historical and contemporary images of Taiwan.

In the age of smartphones, satellite data shows us the world in real-time to an accuracy of up to 30 centimeters per pixel with just the tap of an app. How can traditional maps, produced by hand, compete with that?

Judging by the reactions on social media to a stunning Taipei street map created by British artist Tom Parker last December, the art of mapmaking is neither dead nor forgotten. Parker’s Facebook page was inundated with likes and comments following a post unveiling the new map, and he has since been wooed by local media, including the Taiwan editions of

Harper’s Bazaar

and

Elle

magazines. The map – which was first published as a puzzle in June and is set to be released as a print later this year – is a mad medley of life in the capital, complete with all the key sights and carefully crafted details, such as the giraffe incinerator by Taipei Zoo and scooters buzzing along the capital’s streets.

Hand-drawn maps remain potent tools used to inform, educate, entertain, and delight, as Parker’s work shows. Maps are cultural, political, historical, artistic, and powerful – they can reveal secrets as well as tell lies. And for a place like Taiwan, which struggles to control its identity on the world stage, maps are crucial in defining how the world views it.

Taiwan Business TOPICS

spoke to five individuals who have made valuable contributions to mapping Taiwan in recent years, discussing the enduring appeal of the human-crafted map.

The Historical Maps Artist: Erik Fok

With their fine penmanship, sailing ships, flourishes, navigation lines, and sepia-colored canvases, the maps created by Macanese artist Erik Fok at first glance bear many similarities to ancient mariner charts. But with a closer look, you will notice a modern skyscraper tucked away next to a fort or traditionally built house. Fok, 31, takes great pains to mimic the appearance of historical maps, staining white paper with tea and acrylic paints to “age” it and employing a technical pen for the fine line drawings. He pores over old maps and recreates their designs, supplementing them with imaginary and modern elements.

Macanese artist Erik Fok mixes old and new elements to create “fake history” in his meticulously detailed hand drawn maps. Photo: Erik Fok

“I want to create fake history,” says Fok. “When you see my maps for the first time, you think that they are old. But when you notice the details, you realize they are modern.” His favorite work is one he did of old Tainan, where Taipei 101 incongruously emerges from Fort Zeelandia, a fortress built by the Dutch in the first half of the 17th century.

Fok initiated his series of “fake history” maps back in 2012 in Macau. Rapid land reclamation and manic casino construction had changed his homeland beyond recognition. Fok sought out old records and maps for reference, but still “couldn’t figure out where my location was because so much land had been reclaimed.” Drawing his maps was a way to make sense of all that. “I am inside my maps,” says Fok. “I save my memories inside them.”

Fok has produced around a dozen maps of Taiwan, based partly on his experiences living on the island for three years, starting in 2016 when he was a graduate student at National Taiwan University of Arts. His early maps, which he made as a student, are the size of playing cards.

“I didn’t have much money,” says Fok. “I didn’t have my own studio.” Now that he has become an established artist, his portfolio has expanded. One of Fok’s maps is 3.7-meters long – more than twice the average adult’s height – while others decorate the surfaces of vintage wooden trunks.

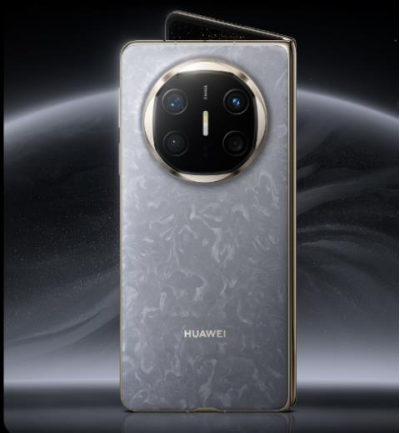

Photo: Erik Fok

Fok is adamant that digital maps are unable to compete with the traditional variety. “We can touch paper; we can feel its temperature – that’s something we can’t do with digital maps.”

The Precise Maps Artist: Tom Rook

British artist Tom Rook’s maps are breathtaking works of intricate detail. They resemble architectural blueprints of a city, down to each individual building. Rook’s maps are vast, black and white, and realistic.

With an eye for detail, Tom Rook maps out cities to better understand them. Both his historical and present-day maps have an antique aesthetic. Photo: Tom Rook

“I seem to have a more Victorian era or a 19th-century-America thing going on in terms of scale and detail,” he says. Similar to Fok, Rook uses mapmaking to understand the places he calls home. It is a way for him to get more closely acquainted with the cities he visited, and a means of recording his time in them, similar to keeping a journal.

“By the time I started drawing Taipei, I’d been living here for about a year, but I was working a lot and hadn’t really explored or connected the city together well,” says Rook. “I felt like a mole popping out of MRT stations, and the city was like a series of disconnected bubbles. I decided to start walking instead of riding the train and photographing what I found in between.”

Photo: Tom Rook

Selecting which buildings and features to include in the map was a delicate operation. “I’ll often move stuff around or shrink certain buildings,” he explains, adding that although he wants people to recognize the places from their lives in his maps, he sometimes needs to make aesthetic decisions. “It’s a hard thing to balance.” He also tries to position landmarks facing outwards so they are recognizable and people can orient themselves. A small map, he notes, can take a month or two to finish, and stresses that “working in pen is slow as there’s no room for error.”

In addition to his Taipei masterpiece, Rook has produced maps of Kaohsiung, Taichung, Chiayi, and an old leprosy sanatorium in New Taipei, among others. His historical maps are geared to periods preceeding significant change, such as the destruction caused by World War II bombing raids, to capture major historical shifts.

“Taiwanese cities have gone through such huge changes that it’s mind-blowing when you see pictures of the streets from the 1930s,” says Rook. He notes that his maps are a form of record-keeping that he hopes will inspire people to preserve what remains of their historical legacy.

“I hope that when people see how much has been lost, they will be more interested in saving what is left,” he continues. “So many interesting streets and buildings have gone in just the [10] years I’ve been in Taiwan.”

The Fantasy Maps Artist: Tom Parker

Tom Parker’s maps exude creativity, and he aims to include intimate details in his works that resonate with Taiwan’s residents. Photo: Tom Parker

Parker’s portfolio is predominantly fantastical, at imagination-on-fire levels. His Instagram feed showcases maps of imagined places: a drawing of a ship with creaky mechanical legs and a menagerie of supernatural animals; Japanese cat warriors; a frog prince mounted on a crow; an Okinawan dinosaur with kissable lipsticked lips; and dogs posing nobly while dressed in Korean hanboks. The same sense of fun is present in his Taipei artwork

.“I love maps as illustrations,” says Parker. “As a visual exploration. Quite simply – something to spend time looking at.”

Parker’s Taipei street map, which runs from Beitou to the Taipei Zoo, required extensive preparation and took around a year for him to complete while working part-time.

“I printed out a standard online map of the area and spent quite a long time pinpointing places I wanted or felt I needed to include,” he says. “Then I had to slightly warp and juggle the whole city to make sure I could fit everything in, though it’s all more or less in the correct place. From there, I just placed a grid over the whole ‘plan’ and started drawing it out large, on individual sheets to scan and jigsaw back together in Photoshop.”

The process demanded much simplification of the map. Overland MRT tracks are single-rail, and the Shida and Ximending areas are squashed, for example. A lot is missing, but there was no way to include everything, he notes. “The map is big, but Taipei is huge.”

Photo: Tom Parker

Parker, 46, who married his Taiwanese girlfriend in 2018 and has lived on the island for about five years, wanted his creation to be more than just a tourist map. He made sure to include intimate details about the city that would resonate with residents, crowdsourcing on his social media for ideas on what to include.

“Adding little places and even characters, like the Pokemon Grandpa on his bicycle with dozens of mobile phones, and a few little shops and cafés that I’m familiar with adds to a feeling for the city beyond pointing out the big flashy parts that come with a tourist map.”

Photo: Tom Parker

Parker’s love for Taipei comes through clearly in his work. It is noticeable in every cheeky bird, ripple on the river, yellow taxi, and jaunty skyscraper. He has already started working on his next project – a map of the southern city of Tainan.

The Playful Maps Artist: Chen Yu-lin

The maps of Taiwanese artist Chen Yu-linare printed into books. She has produced one volume on Taiwanese cities and another plotting Taiwan’s national parks, both aimed at children by using playful and boldly colored drawings. But her style of graphic art, sprinkled with plants, animals, and people engaged in various activities, is also highly popular among adults in East Asia.

As a mother of two young children, now two and six, Chen was inspired to make a book of maps about Taiwan after finding few of them available in stores.

Chen Yu-Lin’s maps focus on people and cats. She creates them in the hopes that her artwork will evoke emotions from viewers. Photo: Chen Yu-lin

“I wanted to show Taiwanese children the place where they were born,” she says. But more than place, maps should be about people, Chen stresses.“The most important thing about my maps is the people who live there. Maps are for people – when you open a map, you imagine the kinds of people you will see there. They could be people who go to church or people who go to the beach.”

People – and cats – are the focus of of Chen’s artwork. Plump felines can be found sunbathing on rooftops, leaning against forest trees, resting on floating glaciers, and riding bicycles, scooters, and even camels.

Chen’s national park book, shortlisted for the 2019 World Illustration Awards, displays scenes of nature and local wildlife. But they are also dotted with tableaus familiar to anyone who has gone hiking in those areas. There are families on day trips, friends using selfie sticks to take photos, a photographer with a camera loaded with a telephoto lens larger than his body, and earnest climbers armed with trekking poles.

Photo: Chen Yu-lin

Following the publication of her works, Chen would slip into bookstores and eavesdrop on customers who were leafing through her work. “The first thing they do is open the book to the page where they live, or point to the place that they want to go next time,” says Chen. “I really love that moment because they are truly feeling something.”

The Map Academic: Jerome F. Keating

U.S. writer Jerome F. Keating does not make maps, but as the dust jacket blurb to the 2011 edition of his

The Mapping of Taiwan: Desired Economies

, Coveted Geographies makes clear, he has “always liked maps.” The book, republished in 2017 in an English-Chinese bilingual format, is a richly illustrated voyage spanning more than 500 years of Taiwan’s history as seen through its maps. Keating explores how they convey historical, cultural, and political meaning far beyond the simple delineation of landmasses.

Long-time Taiwan resident Jerome F. Keating has written six books about the island. In The Mapping of Taiwan, he discusses how maps can influence the way people view a place and vice-versa. Photo: Jerome F. Keating

One of the most fascinating parts of the book is a series of sketches of Taiwan throughout the ages, reflecting progress in navigational and mapmaking skills as well as growing global interest in the island itself, both as a trading partner (desired economy) and as a place to occupy (coveted geography). It begins with a Spanish map from the 16th century where Taiwan is drawn in an oddly oblong shape, moves on to a 17th century English map displaying it as three distinct islands, and then to the more accurate and familiar leaf shape by the 18th century.

Earlier in the book, a French map, also from the 18th century, shows only the western coastal sliver of Taiwan in the shape of a watermelon rind. This indicates that only that portion of Taiwan belonged to China at the time, while the other invisible half was the realm of the indigenous peoples.

Even old maps with errors can be of use, according to Keating, who has lived in Taiwan for decades. “I like some maps, even if they are inaccurate, because they reveal how much knowledge Europeans had gained about Asia in the early 1500s,” he says. “People mapped areas that they traded with much more accurately than areas that they didn’t.”

Photo: Jerome F. Keating

At the time, European countries had few exchanges with Korea and Japan. As a consequence, their maps of Korea depicted it as an island rather than a peninsula, and Japan as a half-moon. Parts of the ocean were estimated incorrectly.

For Taiwan, maps are highly political due to China’s claim on the island – not only through the names or colors used for Taiwan, but also in how it is framed in relation to the rest of the region.

“Most maps show Taiwan as close to China and usually cut off the island chain that it is a part of,” says Keating. “This influences thinking on whether Taiwan is part of China.” He suggests that “a map just showing the island chain coming down from Japan and then extending to the Philippines (i.e., the different tectonic plates that form the island) and not even showing the continent” would help to differentiate Taiwan as a body separate from China. “Maps constantly influence our thinking, even at a subconscious level,” he notes.