A surge in heat-related deaths amid record-breaking summer temperatures offers a “glimpse into the future” and a stark warning that one of America’s largest cities is already unlivable for some, according to its new heat tsar.

Almost 200 people died from extreme heat in Phoenix in 2020 – the hottest, driest and deadliest summer on record with 53 days topping 110F (43C) compared with a previous high of 33 days. Last year there were fewer scorching days, but the death toll remained staggeringly high, with people experiencing homelessness and addictions dying disproportionately.

Phoenix, the capital of Arizona, is accustomed to a hot desert climate, but day and night temperatures have been rising due to global heating and the city’s unchecked development, which has created a sprawling urban heat island.

Scorching temperatures have made summers increasingly perilous for the city’s 1.4 million people, with mortality and morbidity rates creeping up over the past two decades, but 2020 was a gamechanger when heat related deaths jumped by about 60%.

Last year, after another deadly summer, the mayor announced the region’s first dedicated unit to tackle the growing hazard of urban heat, which also threatens the city’s economic viability.

“Phoenix is already unlivable in summer for far too many of our residents, who literally didn’t live because it was too hot. Every death is preventable and shows that there’s much much more for us to do to make the city livable and comfortable for everyone,” said David Hondula, the recently appointed director of Phoenix’s heat response and mitigation office.

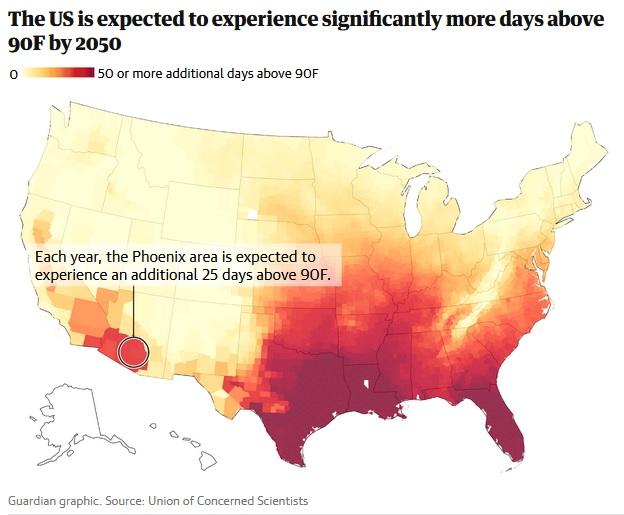

“2020 was a glimpse into the future – it’s the type of summer that could be normal by 2050 or 2080, so that’s what we need to be prepared for so that Phoenix is livable and thriving.”

Phoenix is the country’s hottest and fifth most populous city, where businesses and people began flocking when affordable air conditioning became available in the 1950s. The population growth has led to a huge expansion in concrete infrastructure (buildings, roads and carparks) and a reduction in green areas, which has created heat islands – dangerously hot urban areas that absorb and re-emit the sun’s heat more than natural landscapes.

Between 95% and 99% of homes in Phoenix have air conditioning, yet in some surveys, as many as a third of residents in the larger metro area, more than a million people, have reported experiencing adverse effects from the heat – suggesting many cannot afford to power or repair their cooling units.

Hondula will lead a four-person team with two broad goals: protecting residents when it’s very hot (the heat response part), and coming up with long-term strategies to cool the city and make it more comfortable (the mitigation part). Both require better data, better coordination across government, and money.

For instance, the local health department has a highly-rated surveillance system but even then, the final tally and details of summer heat related fatalities are published the following February or March. “That leaves a very short window to plan for the next hot season, and deaths represent only the tip of a big iceberg … We have almost no knowledge about what conditions people experience in their homes,” said Hondula, a climate and health scientist who has spent more than a decade investigating the risks and vulnerabilities associated with heat.

The team’s success will be measured in deaths and illness numbers, but the problems and solutions are interconnected: saving lives will require redesigning the city’s heat-trapping concrete landscape, as well as improving access to cooling centers, hydration stations and paramedics.

There are quick fire changes, or low-hanging fruit as Hondula puts it, which he thinks could have some immediate impact. For example, too many people have trouble accessing cooling centers when they need them; more signs and longer opening hours would help, as would public health campaigns asking residents who call 911 to stay with the person until first responders arrive.

But it will take much broader changes to tackle the root causes driving deaths in the most vulnerable group: middle-aged men experiencing homelessness and substance misuse problems. “To reduce deaths, we need to be thinking way upstream and take steps to ease the housing affordability crisis and improve access to substance abuse and recovery services.”

Hondula recently submitted the 2022 heat response plan to city hall, in an attempt to coordinate the existing patchwork of services. “I’m impressed by the number of programs but the death and illness numbers are moving in the wrong direction, so there’s a disconnect we need to address,” he said. “If we mean to take a hazard seriously, relying on good fortune, luck and happenstance is not the best model.”

Mitigation will be focused on trees and infrastructure, which will be led by an urban forester and a built environment expert who are yet to be hired.

Planting trees is broadly popular and has been touted as a relatively painless fix to combating climate change by world leaders including Donald Trump, Britain’s Boris Johnson and Turkish president Recep Erdoğan.

In Phoenix, the city published a tree master plan in 2010, pledging to increase canopy cover to 25% by 2030 (from an estimated 11% to 13% at the time). The city is not on track to meet that goal, and the target may eventually be revised to reflect the city’s broader sustainability and equity goals such as targeting under-shaded neighborhoods and public transit routes where people walk and wait.

“Trees are an important part of the plan which residents have been asking for for years, but they aren’t a cure-all for the city,” Hondula said. “But if we could have 30% of a 20-min walking path shaded, it would provide health protection for most summer days,” said Hondula.

Money is an issue. So far, the unit doesn’t have a budget for programs but there are options.

The heat unit has bid for a slice of the city’s second American rescue plan installment, due in May, to fund a residential tree planting program targeting 25 neighborhoods with the least shade.

Engineered shade such as cool pavement – a reflective compound painted over asphalt that reduces the amount of sun absorbed – is being piloted across the city. The results are encouraging, but again Hondula warns against clinging to this as an easy fix.

“I don’t think we can go all-in on cool pavement because that commits us to hard infrastructure in places where there might be better uses,” he said. “Our office needs additional land for tree planting that might be land that is currently streets … but any talk about lane reduction or lane removal is a sensitive conversation.”

Another sensitive and critical area is the city’s property development gravy train, which for years has been forging ahead faster than its ad hoc mitigation efforts. Hondula acknowledges that getting to grips with the gaps and loopholes in every part of the building process – from zoning and permitting to shade requirements and enforcement – will take time.

“There’s a very fast train moving ahead with respect to development and it may be too late for the heat mitigation office to intervene in existing plans. It could be three years down the road before our fingerprint shows up, but we have to accept that these are longer term processes and get working as quickly as we can.”

Climate disasters such as deadly heatwaves, wildfires, drought and torrential rain storms are increasingly frequent, costly and deadly and experts agree that slashing greenhouse gas emissions is the only way to limit global heating.

But towns and cities are not helpless. In fact, Hondula argues, tackling urban heating could help turn around the city’s livability decline. “All cities have tiny hands on the big lever [of global heating] but the dominant driver of regional climate change has been urbanization, and that’s a lever we do have in our hands as local governments.

“Some modeling suggests with widespread deployment of cooling technologies like trees and reflective surfaces, we could end up with a city in the future that is cooler than we have today even with continued global scale warming, which is a very encouraging sign.”