This is the dawn of the golden age of predictive technologies. Billions of sophisticated algorithms powered by vast computers enable forecasters to process ever-larger amounts of data. In a range of fields from weather to medicine to business, our ability to draw conclusions about the future should be better now than at any stage in history.

And yet, it isn’t. Indeed, our recent past – from COVID-19 to the great financial crisis – could be viewed as a history of our failure to predict the future.

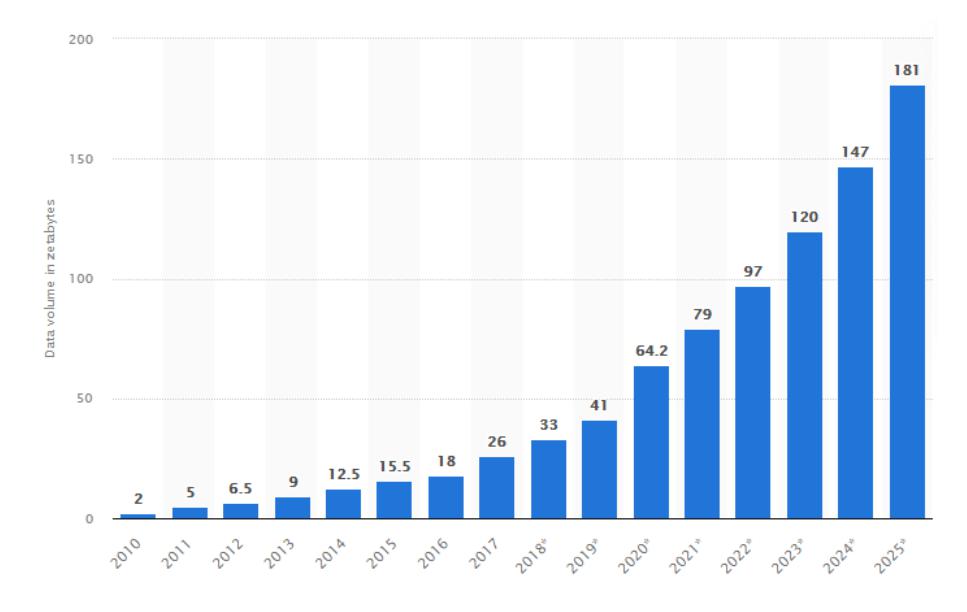

The advent of technology and the resulting change in our ability to foresee potential future events has coincided with an exponential increase in the range and variety of possible outcomes. The same advances in technology that have enabled us to be more certain about our decisions have increased the complexity of the landscape in which those decisions take place. The chart below, which illustrates the growth of data since 2010, tells two stories: one is about the amount of information we have on which to base our decisions, and the other is about the potentially overwhelming nature of the size and complexity of this data.

How can we begin to seize back the advantage in our attempts to see what lies around the corner? We must recognize that the tools we used in the past to model future outcomes were predicated on a steady-state environment. To engage with a future of exponential change, we need our tools to be as dynamic as the world whose outcomes they are seeking to predict. We must acknowledge when using data to make predictions that the world of tomorrow is going to be dramatically different from the world of today.

In practical terms, this involves weaving technology into as many areas of our lives as possible, recognizing the spheres in which the speed, efficiency and sophistication of technology far exceed the capabilities of analogue alternatives. It also requires a change in mindset.

In this article, I’d like to consider what the speed of technological change has done to our conception of the future of risk. Modelling risk is another way in which we seek to map the shape of the future, the most commonplace of our attempts at prediction. Living in a world of exponential change demands a radical alteration of the way we visualize the future and a dynamic reprogramming of our understanding of risk. We must abandon many of the tenets by which we understood the past and instead adopt new ways of conceptualizing the future, embracing change as the engine of innovation and growth.

Think about Moore’s Law, the observation made in 1965 by Intel co-founder Gordon Moore that the number of transistors in an integrated circuit doubles roughly every two years. This exponential relationship has long been held as a proxy for the growth of processing power and has been used to illustrate to computer scientists both the range and limitations of their ambitions. Moore’s Law has begun to break down, though, and it is breaking down as a result of the technological innovation that it seeks to predict.

Have you read?

With the arrival of AI and alternative processors, transistor count simply isn’t a useful representation of processing power anymore. Chips have become smaller and smaller, have moved from 2D to 3D, employ increasingly sophisticated and specialized materials in their construction, but traditional central processing units (CPUs) are no longer the frontline of technological innovation. A recent study by Silicone Angle showed that a strict definition of Moore’s Law, which would require transistor numbers to grow at an annual rate of 40%, had slowed to below 30% by 2020. And yet, processing power, taking into account the combination of traditional CPUs with AI and alternative processors, is growing at more than 100% each year. Everywhere we look, the rules of yesterday are being rewritten by the significant rise of technology.

We are at an inflection point in the science of prediction. Humans often hold fixed notions about the operation of the world and can be inflexible when it comes to going down new paths. Some segments of the financial services industry were slow to adopt technology, but skeptics are finding their arguments challenged by increasing evidence that computers, especially when paired with human talent, can act more effectively to find opportunity in the markets. If the past decade has been about the massive accretion of data, the next decade may well be about refining our ability to process and utilize data. We are just beginning to understand what technology will make possible when it comes to prediction.

Where does this leave us as we look to the future? We are only at the start of the technological revolution. The coming years will require even greater dynamism and flexibility from institutions, thinkers and workers. Exponential growth requires us all to undergo a daily process of discarding the certainties of the past in order to embrace a future of radical change.