Croquet is an intriguing new browser-based system for creating 3D “microverses,” described as “independent, interconnected web-based spaces and worlds created on the Metaverse.” The technology was developed by David A. Smith, a computer scientist with 30 years of experience in the VR and AR industry — including creating the set visualization software behind James Cameron’s 1989 movie, “The Abyss”.

In an interview with Smith (CTO) and the company’s CEO, John Payne, I discovered how Croquet works — including its JavaScript frontend — and why the founders believe the web will underpin the emerging metaverse.

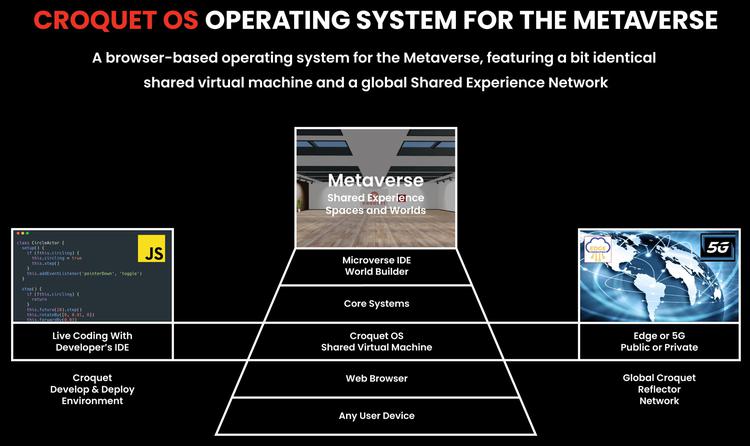

There are several aspects to Croquet that I’ll outline in this post: the virtual world that the user sees, the “microverse IDE” that JavaScript developers use to create content for it, and the “reflector network” that runs the system. Let’s first look at the virtual world.

The Browser OS

The 3D world that the user inhabits works via a “virtual machine operating within the browser,” according to the company — this is why it’s called an OS (operating system). A user enters the virtual world “from any URL or QR code […] using web, mobile or AR/VR devices.”

In the demo conducted by Smith and Payne, I clicked on a URL they gave me to enter a 3D world on my computer’s browser, and then entered the same scene with my phone’s browser by scanning a QR code. The user experience is reminiscent of Second Life, except that with Croquet you don’t need to download a special 3D viewer software program — it’s all inside the browser.

Croquet works across devices.

“We see the metaverse as an extension of web and mobile,” said Payne, “rather than everyone running around with a VR headset on their head, bumping into things. What our customers are telling us is that they want a totally cloud platform solution, where anyone with any device can log in anytime.”

Their customers, by the way, are initially enterprise — for example, the Japanese conglomerate Hitachi is using the 3D space as “a control room for a mining facility” for staff based in different geographic locations. But Payne said that eventually they hope Croquet will be used by regular people.

“Ten years from now, the web is going to be a 3D place,” he said. “Someone who has a website can build a virtual world — it may be a showcase to look at jewelry, it may be a training room…it can be a bunch of different things — and then publish it to the same web server their website runs on, expose it as a link or a button, or a portal.”

Reflectors

Croquet has had a long back-history. According to Smith, he first began developing the idea when he met Alan Kay, the personal computing pioneer who worked at Xerox PARC in the early 1970s. Smith met him in the early 90s, when Kay was a senior fellow at Apple.

“He and I started thinking about what [are] the next steps in computing,” Smith said. “I had obviously done a lot with 3D, but it was pretty clear to both of us: it was not just 3D, but had to be collaborative 3D, interactive 3D.”

In the origin story page of its website, Croquet OS states that 1994 was the year Smith created “the first prototype of what will later become Croquet,” describing it as “the first 3D collaboration space, demonstrating live shared video and smart collaborative objects.” Kay came back into the picture in 2001, when Smith, Kay and two others (David Reed and Andreas Raab) formed “the Open Croquet Project,” which aimed to “create the first replicated computation platform.”

Replicated computation is a key part of the current Croquet system and it achieves this via software it calls “reflectors.” In its documentation, Croquet describes these reflectors as “stateless, public message-passing services located in the cloud.” They are hosted on edge or 5G networks.

“We have deployed around the world, on four continents, what we call a reflector network,” explained Payne. “And what that is, is basically a whole bunch of small micro-servers that coordinate and synchronize the activities of everyone who’s participating in a session.”

Croquet system diagram.

In our demo, Payne and Smith were located in the United States, while I was in the United Kingdom (about 150 miles from London). The nearest reflector to me was in London, so that was how my participation in the Croquet virtual world was coordinated. But it’s not just users on different continents that benefit from the reflector network, it also means a single user can participate with multiple devices. In the demo, I was asked to open the virtual world on my phone as well as my computer (this was a little confusing, as I had two separate views — yet I was a single user).

Smith described this as “a shared simulation system.” When a user interacts with it, he said, “that message gets sent to the reflector and bounces off the reflector to all the other participants. So when you’re interacting with it on your PC, that message is also going to wind up on your phone.”

The IDE

Finally, let’s look at the Microverse IDE, from which developers can create 3D experiences.

There’s a new vocabulary to learn in order to program in Croquet’s IDE. Objects in this virtual world are called “cards” (inspired by the famous 1980s and 90s Apple Macintosh program, HyperCard), which “can be constructed by simply dropping an SVG or 3D model into the world.” Interaction with cards is defined by “behaviors,” while “connectors” enable cards “to access external data streams.”

“Bill Atkinson’s model of computing and how things should work was hugely influential,” said Smith, referring to HyperCard’s creator. “Alan Kay was his main champion at Apple. We saw that [model] as like, that’s the right way to think about creating and constructing virtual worlds. So that’s why we call it a card. We’re gonna change the name, probably.”

Later in the demo, Smith showed me a 3D display of Bitcoin prices. This object was made up of three cards, he informed me: a card connecting to a feed of real-time Bitcoin prices, a bar graph card, and a card showing the Bitcoin logo.

Bitcoin chart in Croquet.

“The idea of HyperCard is that you can plug these things together, and that’s what’s going on with this,” Smith said. “What’s nice about all that is you don’t have to explicitly connect these things. All you do is say: this is a parent of that card, and then you use a publish-subscribe model so that they [the parent] can listen to what’s going on. So creating these applications is extremely easy and fast.”

Under the hood, Croquet’s frontend uses web sockets, REST interfaces, Three.js (a 3D JavaScript library), and WebGL (a JavaScript API for rendering 3D graphics). WebGPU is on the horizon, too. The 3D physics is done with the Rapier Physics Engine, an open source Rust-based engine running in WebAssembly that Croquet has supported since its inception. Other technologies used include Crypto.js (a collection of cryptographic algorithms implemented in JavaScript), end-to-end encryption via AES-CBC with HMAC-SHA, and Resonance Audio for spatial sound.

“The real idea of the system is it should be always be live and always collaborative, not just in the deployment but even the development side,” said Smith. “So you and I can do pair programming, for example.” He gave an example of me dropping in a new 3D object and then he would do the scripting for it.

Example of coding inside Croquet. Pink flamingo optional.

An Open, Collaborative 3D World? Sign Me Up!

Croquet is a complicated platform, and the demo wasn’t without technical glitches. But I very much admire that this is a web-based system. The company’s ambition is to make Croquet an open “microverses” alternative to the likes of Meta and its dream of a single, much larger (and likely proprietary) metaverse.

I also like the interactive nature of the Croquet platform, that developers can use it to collaborate with other developers inside the virtual world. That vision not only aligns with Alan Kay and the Xerox PARC crew of the early 1970s, but their predecessors at SRI, led by Douglas Engelbart (who was mentioned in Croquet’s origin story as an inspiration).

The World Wide Web itself has come closest to achieving Engelbart’s original vision, and perhaps Croquet will help adapt the web to the emerging 3D world.

Lead image via Shutterstock; other images via Croquet.