reader comments

230

with 104 posters participating, including story author

Share this story

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Reddit

The Chromium browser—open source, upstream parent to both Google Chrome and the new Microsoft Edge—is getting some serious negative attention for a well-intentioned feature that checks to see if a user's ISP is "hijacking" non-existent domain results.

The

Intranet Redirect Detector

, which makes spurious queries for random "domains" statistically unlikely to exist, is responsible for roughly half of the total traffic the world's root DNS servers receive. Verisign engineer Matt Thomas wrote a lengthy APNIC blog

post

outlining the problem and defining its scope.

How DNS resolution normally works

Enlarge

/

These servers are the final authority which must be consulted to resolve .com, .net, and so forth—and to tell you that 'frglxrtmpuf' isn't a real TLD.

Jim Salter

DNS, or the Domain Name System, is how computers translate relatively memorable domain names like arstechnica.com into far less memorable IP addresses, like 3.128.236.93. Without DNS, the Internet couldn't exist in a human-usable form—which means unnecessary load on its top-level infrastructure is a real problem.

Loading a single modern webpage can require a dizzying number of DNS lookups. When we analyzed ESPN's front page, we counted 93 separate domain names—from a.espncdn.com to z.motads.com—which needed to be performed in order to fully load the page!

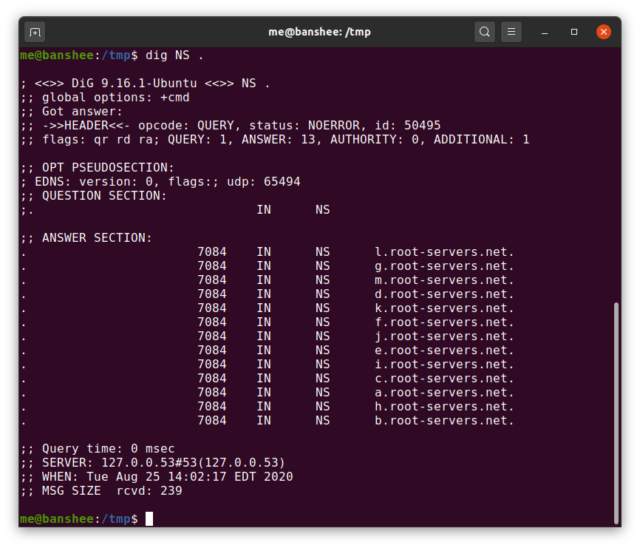

In order to keep the load manageable for a lookup system that must service the entire world, DNS is designed as a many-stage hierarchy. At the top of this pyramid are the root servers—each top-level domain, such as .com, has its own family of servers that are the ultimate authority for every domain beneath it. One step above

those

are the actual root servers,

a.root-servers.net

through

m.root-servers.net

.

How often does this happen?

A very small percentage of the world's DNS queries actually reaches the root servers, due to the DNS infrastructure's multilevel caching hierarchy. Most people will get their DNS resolver information directly from their ISP. When their device needs to know how to reach

arstechnica.com

, the query first goes to that local ISP-managed DNS server. If the local DNS server doesn't know the answer, it will forward the query to its own "forwarders," if any are defined.

If neither the ISP's local DNS server nor any "forwarders" defined in its configuration have the answer cached, the query eventually bubbles up directly to the authoritative servers for the domain

above

the one you're trying to resolve—for

arstechnica.com

, that would mean querying the authoritative servers for

com

itself, at

gtld-servers.net

.

Advertisement

The

gtld-servers

system queried responds with a list of authoritative nameservers for the

arstechnica.com

domain, along with at least one "glue" record containing the IP address for one such nameserver. Now, the answers percolate back down the chain—each forwarder passes those answers down to the server that queried it until the answer finally reaches both the local ISP server and the user's computer—and all of them along the line cache that answer to avoid bothering any "upstream" systems unnecessarily.

For the vast majority of such queries, the NS records for

arstechnica.com

will already be cached at one of those forwarding servers, so the root servers needn't be bothered. So far, though, we're talking about a more familiar sort of URL—one that resolves to a normal website. Chrome's queries hit a level above

that

, at the actual

root-servers.net

clusters themselves.

Chromium and the NXDomain hijack test

Enlarge

/

Chromium's "is this DNS server f'ng with me?" probes represent about half of all the traffic reaching Verisign's DNS root-server cluster.

Matthew Thomas

The Chromium browser—parent project to Google Chrome, the new Microsoft Edge, and countless other lesser-known browsers—wants to offer users the simplicity of a single-box search, sometimes known as an "Omnibox." In other words, you type both real URLs and search engine queries into the same text box in the top of your browser. Taking ease-of-use one step further,

it doesn't force you to actually type thehttp://

or

https://

part of the URL, either.

As convenient as it might be, this approach requires the browser to understand what should be treated as a URL and what should be treated as a search query. For the most part, this is fairly obvious—anything with spaces in it won't be a URL, for example. But it gets tricky when you consider intranets—private networks, which may use equally private TLDs that resolve to actual websites.

If a user on a company intranet types in "marketing" and that company's intranet has an internal website by the same name, Chromium displays an infobar asking the user whether they intended to search for "marketing" or browse to

https://marketing

. So far, so good—but many ISPs and shared Wi-Fi providers hijack every mistyped URL, redirecting the user to an ad-laden landing page of some sort.

Generate randomly

Chromium's authors didn't want to have to see "did you mean" infobars on every single-word search in those common environments, so they implemented a test: on startup or change of network, Chromium issues DNS lookups for three randomly generated seven-to-15-character top-level "domains." If any two of those requests come back with the same IP address, Chromium assumes the local network is hijacking the

NXDOMAIN

errors it should be receiving—so it just treats all single-word entries as search attempts until further notice.

Advertisement

Unfortunately, on networks that

aren't

hijacking DNS query results, those three lookups tend to propagate all the way up to the root nameservers: the local server doesn't know how to resolve

qwajuixk

, so it bounces that query up to its forwarder, which returns the favor, until eventually

a.root-servers.net

or one of its siblings has to say "Sorry, that's not a domain."

Since there are about 1.67*10^21 possible seven-to-15-character fake domain names, for the most part

every

one of these probes issued on an honest network bothers a root server eventually. This adds up to a whopping

half

the total load on the root DNS servers, if we go by the statistics from Verisign's portion of the

root-servers.net

clusters.

History repeats itself

This isn't the first time a well-meaning project has

swamped

or nearly swamped a public resource with unnecessary traffic—we were immediately reminded of the long, sad story of D-Link and Poul-Henning Kamp's NTP (Network Time Protocol) server, from the mid-2000s.

In 2005, Poul-Henning Kamp—a FreeBSD developer, who also ran Denmark's only Stratum 1 Network Time Protocol server—got an enormous unexpected bandwidth bill. To make a long story short, D-Link developers hardcoded Stratum 1 NTP server addresses, including Kamp's, into firmware for the company's line of switches, routers, and access points. This immediately increased the bandwidth usage of Kamp's server ninefold, causing the Danish Internet Exchange to change his bill from "Free" to "That'll be $9,000 per year, please."

The problem wasn't that there were too many D-Link routers—it was that they were "jumping the chain of command." Much like DNS, NTP is intended to operate in a hierarchical fashion—Stratum 0 servers feed Stratum 1 servers, which feed Stratum 2 servers, and on down the line. A simple home router, switch, or access point like the ones D-Link had hardcoded these NTP servers into should be querying a Stratum 2 or Stratum 3 server.

The Chromium project, presumably with the best intentions in mind, has translated the NTP problem into a DNS problem by loading down the Internet's root servers with queries they should never have to process.

Resolution hopefully in sight

There's an open

bug

in the Chromium project requesting that the Intranet Redirect Detector be disabled by default to resolve this issue. To be fair to the Chromium project, the bug was actually opened

before

Verisign's Matt Thomas drew a giant red circle around the issue in his APNIC blog

post

. The bug was opened in June but languished until Thomas' post; since Thomas' post, it has received daily attention.

Hopefully, the issue will soon be resolved—and the world's root DNS servers will no longer need to answer about 60 billion bogus queries every day.

Listing image by

Matthew Thomas